Wars come and go, but their legacies remain. Photographer Giles Duley’s focus goes beyond war itself. Throughout his career, Duley has documented the effects of war — instability, displacement, trauma, in-fighting, refugees and casualties. Regardless the region, conflict brings the same core damage … and it is people who wear the scars and carry the burden of memory. From the front lines in Afghanistan to the shores of Lesvos to South Sudan, Duley came to understand the many fallouts of war. And then, a few years ago, familiarity gave way to personal injury and trauma.

In 2011, Duley was documenting the civilian impact of war in Afghanistan when he stepped on an Improvised Explosive Device (IED). He lost both legs and his left arm. After 18 months, over 3o operations and rehabilitation he was determined to continue working. And he did, returning to Afghanistan to complete the work he had started before the accident. Some of the work from that trip is included in One Second of Light, a book of works spanning 10 years of his career.

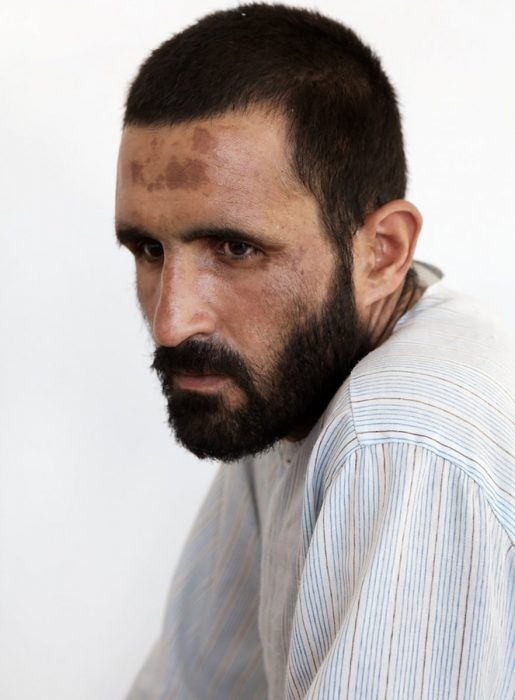

Farid, who was injured by a US grenade, enjoys the sun and fresh air outside his ward. He was injured when caught in the cross-fire between the Taliban and a US patrol. His father had taken him to the nearest American patrol base but they had refused to treat him on the grounds that he might have been a Taliban. His father had then driven him to EMERGENCY’s Surgical Centre, where he received treatment to serious head and stomach injuries. Kabul, Afghanistan — 2012

Giles Duley’s photographs of people caught up in the effects of war are powerful in their ability to show both courage and humility. The photos are striking. They can be unsettling. Duley finds humanity in situations that are often the worst we can imagine.

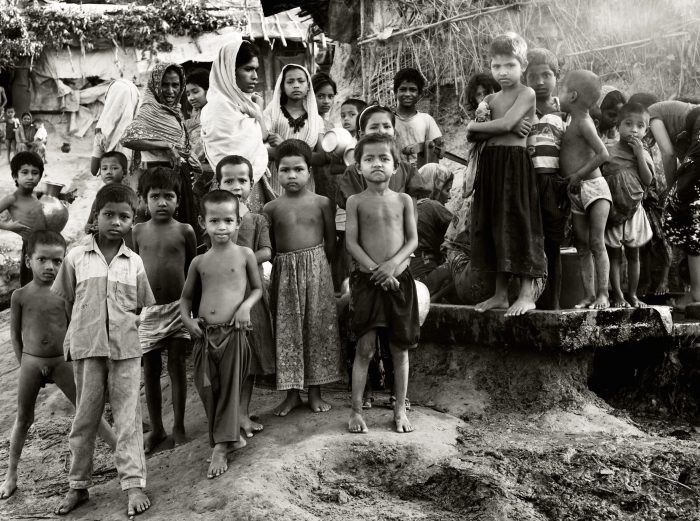

He reflects the dignity of people teases out the common traits among sitter and audience, among us all. These are not disconnected people half a world away; the people in his portraits could just as well be our relatives, our neighbors, our friends. Refugee children wear clothes we could’ve placed upon our own children. We encounter men, women, children, or entire families who fled their homes, their countries, and their way of life. Where they could they kept each other close.

Many people in Duley’s images have been injured and face a limited number of medical facilities providing emergency trauma or intensive care. It is not easy to make photographs like those in One Second of Light. Duley chooses to put his emotional and financial resources into photographing what must seem like at times an endless stream of war survivors. He does so because the issue is not going away. It is sometimes necessary to be a voice of dissent for the sake of humanity.

Sediqullah, 10, awaits surgery on his injured hands. His hands had been badly damaged when playing with a bomb fuse he had found. He lost several fingers. A third of EMERGENCY’s patients are children, and in Afghanistan, amputations of the fingers, toes, hands and feet are especially common. Spending much of their time outside working or playing, children are extremely vulnerable to landmines and IEDs.

While Giles Duley works with quiet humility, he speaks loudly through his photographs. He’s an advocate for greater humanity and greater understanding across borders, across continents.

“At a time when the Internet is full of images meant to shock and divide, it seems more important than ever to focus my camera on the things that unite us,” says Duley. “Whilst some document the differences between us, I am fascinated by what makes us the same. Humanity is universal and wherever I travel, I see the same hopes and dreams, the same intimacies and values.”

Before his incident with the IED, Duley was used to being a fly-on-the-wall. He was nimble and ducked in and out of situations with ease. Now he has two shiny new legs, one arm, and initially had trouble balancing his heavy camera on the stump of his left arm. He remains discreet but he’s less anonymous than he once was.

After a couple of weeks shooting photos, Duley discovered that his new condition helped create stronger connections with his subjects; he and the people he photographs relate their shared experiences and long discussions.

Dolly, 24, was attacked with acid after a failed marriage proposal in 2001. The Acid Survivors Foundation (ASF) is an inspiring hospital, but its staff, many who are survivors themselves, are what makes it truly special.

Tofazzari, 42, was attacked with acid over a property dispute. He was blinded, and left speechless due in part to the psychological trauma. Despite the horrifically brutal nature of these attacks, the staff of ASF have made it a place where nobody is pitied, none see themselves as victims; and remarkably created a place that is full of hope, laughter and companionship.

Duley says that photographing injured people is intrusive and difficult, and it comes with a responsibility. Somebody once asked stupidly (his words) if it was worth losing his legs to get the photographs of the conflict and the people in Afghanistan. His response was that no one image is worth the cost of losing his legs — but the principle is.

“Whilst some document the differences between us, I am fascinated by what makes us the same. Humanity is universal and wherever I travel, I see the same hopes and dreams, the same intimacies and values.” — Duley

Despite everything that has happened to him, he remains committed to telling the stories of people in need, or people who have lost their own legs, or worse; and they didn’t lose them in order to make a photograph. But it is the quiet, dignified courage of others to endure some of the most frightening things imaginable, and to do what it takes to survive, that compelled Duley to make the images. He worked not out of self-interest, but rather as an advocate for those who suffer without voice.

“Whatever the rights and wrongs of this war, I can’t help feeling that if we prosecute a war in another country, we have a duty of care to civilians caught up in it,” he says. “As humans, it must be our duty to help those in need.”

Said Karim, a stonemason who lost his legs when his car drove over a landmine. While recovering from his horrific injuries, Said’s main concern was how he would not support his family. Said and his brother were the bread-winners for an extended family of eight.

Photographers have always worked with slices of time. Duley wrangles disparate moments to deliver a broad powerful message.

“Whilst we see stories from Angola to Bangladesh, Afghanistan to Sudan; all we are seeing is a flicker of others’ lives,” he says. “If you add the combined shutter speeds of these images — they equate to nothing more than a moment of time — One Second of Light. Photography can give us some insight, but it’s just a window you are looking through momentarily. For those caught in these stories, the time and their suffering is a constant.”

For every split second of each frame, Duley spent hours or days with his subjects. He has adopted an approach to his many portrait sessions.

“I always, always have to think of dignity in the first instance. I have a strange rule: I always think of my sister, or anybody close to me, and I think, ‘How would I want them to be photographed if they were in such bad circumstances?’ It’s a weird thing, but I see it that way. How would I want somebody I love to be photographed? I would want them to be photographed with dignity.”

Kutupalong Camp, Bangladesh, 2009. People gathered at one of the few water collection points in Kutupalong Camp; no mare than a broken pipe. The water pollution was five times over the safe limit.

It takes courage to be an advocate for something greater than themselves. It requires something more than just the absence of fear. Any fool can be fearless. The essence of courage comes from the best version of ourselves, and the strength to do the right thing, to do hard things for the lasting benefit of others. It takes this type of courage to photograph people caught in the effects of war, in hopes that the quiet pairing of empathetic images and words speaks louder than the bloody spectacle of war.

Leave a Reply