blog

Book Review: A Place of Our Own by Iris Hassid

The Israeli territory is a region full of differences and contrasts which have always attracted the attention of Iris Hassid, a photographer from Tel Aviv who focuses her work on long-term projects related to identity, culture and the representation of a female viewpoint from different social backgrounds.

In A Place of Our Own, Iris Hassid decided to focus her attention on the new generation of young adults of Arab origin to document their daily life. But, above all, she wanted to present women Palestinian-Arab citizens of Israel in a different way than the version she saw portrayed in the media. Hassid began to approach young Arab women on the street to invite them to participate in her new photographic project. Initially, she was rejected by many people. When she met Samar, a film student at Tel Aviv University, the project truly began in 2014. A Place of Our Own follows the daily life of Samar, her cousin Saja (a psychology student), Majdoleen (architecture student) and Aya (specialist in social services and gender studies).

Over a period of 6 years, Iris explored the lives of these 4 protagonists at an intimate and familial level. Sometimes the project was at risk of abandonment; as when the war broke out in Gaza in 2014 and contact with the girls were interrupted for 6 months.

Hassid’s home is close to the university (Ramat Aviv) in Tel Aviv. She was intrigued by the presence of Palestinian students about 8 years ago. She felt It was unusual to hear Arabic spoken on the streets of Tel Aviv because Arab communities are rarely located within big cities and, moreover, those communities are close-knit and somewhat “protective” of members of the community.

“It’s important that you photograph what you see here, in real life, and not how an Arab woman is portrayed in the media. It needs to be a strong feminist project. You grew up in Ramat Aviv, and you didn’t meet any Arabs before us. In recent years you started seeing young Arab women on your street, and you realized that what you learned had been told at school was not the whole truth, not even close.” [Samar]

Most importantly, the work was not a mere documentary project, and it was developed thanks to the mutual trust and confidence established between the photographer and the subjects. They collectively chose the text excerpts to work in parallel with the images across the project. The book should be seen as a collaboration between photographer and subjects.

Samar, Aya, Saja, and Manar, green car, Ramat Aviv. First time photographer Iris Hassid met Samar for a photo shoot, she arrived with her cousin and two close friends. The resulting photograph in a green car captures the young women’s state of happiness. They look confident about the future.

“All the time, people say to me: you don’t look like an Arab…even this Arab guy we had talked to said it. I really don’t get what they expect to see!

In Tel Aviv, when I talk on my mobile phone in Arabic, on the street or in the bus or with friends, people stare at us. Arabic is an official language in this country – why it so strange to hear Arabic on the streets? We are Palestinian Arabs, and we are also citizens of Israel. Whether we want to or not, we have Israeli ID cards and passports.” [Samar]

Flag, Beit Milman Student Dormitories, Ramat Aviv. Tel Aviv University was built on the ruins of the Palestinian village of Sheikh Munis, which – like more villages and refuges in other areas – had been evacuated during the 1948 war of independence for the establishment of Israel. The Palestinians refer to this event as the Nakba (catastrophe), a term not recognized by the government and official institutions of Israel, and most Israelis.

“I don’t relate to Israeli roots, of course, and not so much to Palestinian ones. I won’t go around with a Palestinian flag, or with an Israeli one.

Inside I have a Palestinian identity, but I don’t relate to it in my daily life. I’m not at all a political person. I’m interested in human relations between people.” [Saja]

A Place of Our Own does not claim to faithfully document the lives of these women but wants to represent everyday lives of women who present as strong, yet also fragile. They have a vision of the world and politics, but they are often discriminated against. They also aspire to have normal lives and status in society.

These first-rate women do not accept being seen as second-rate citizens. They are fully part of Israel, whether they feel the rest of the country likes it or not. They are committed, they won’t go anywhere. They are building their lives just as their Jewish counterparts are trying to do.

Hassid’s work highlights women who feel they need to be seen as something other than “Israeli Palestinians” or “Israelis with Palestinian origins”: women who are something new.

What makes the project even more interesting to me, and not stereotypical: a non-traditional, a Jewish photographer wants to immerse herself in the daily freedom and joy of these Arab girls.

A Place of Our Own speaks of feelings and belonging, of human beings with their own identity in search of a space: “a place of our own”, literally. I like the project for its discretion. The photographer is always physically present, but the images feel as if she was invisible. Hassid selects specific shooting choices: moving the shots from the interior spaces to the streets, as if metaphorically moving from the inner world to the outer one of the protagonists. Her choice to use recurring themes in the project was appropriate. There are clues and signs in every image. Cars and bicycles used as symbols of independence, mobility and freedom; flags, walls and olive trees employed as symbols of Palestinian identity.

The Israeli-Palestinian matter is as complex as it is unresolved. This book could be a key to having a more clearer vision of a conflict that despite much discussion, not enough has been said.

Majdoleen, room, on the circular tapestry, the word “Freedom” is embroidered in Arabic, Ramat Aviv. Since the Nationality Law, Majdoleen, whose mother was born in Lebanon and is the second generation of Palestinian refugees, has been troubled by her identity’s definition. She wants to be called an Israeli Palestinian, or an Israeli with Palestinian roots. Though the discrimination of has always been out in the open, the law still hurt Israeli citizens like her.

“That’s why I’m in this photographic project, not because of the political side, but because of the feminist side. To show us as we are. It should be optimistic and yet truthful. I hope it will show that we want to live together, in equality.” [Saja]

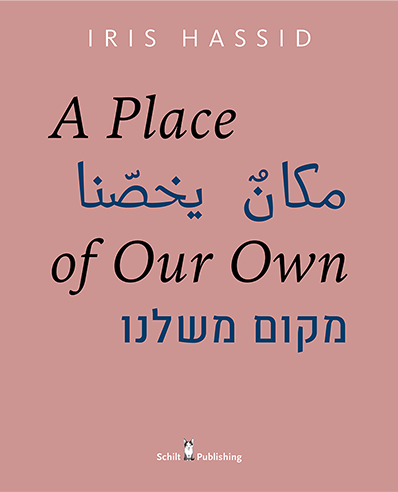

A Place of Our Own

by Iris Hassid

The book, published by Schilt Publishing, has 167 pages and includes about 90 photographs.

The designer, Victor Levie, did a fantastic job and worked together with Iris Hassid throughout the sars-cov2 pandemic, via email and Skype.

The book also includes essays by researcher, lecturer, feminist activist Manal Shalabi (on the representation of the body as a symbol of openness and demonstration of the change taking place in Arab society and transition from its patriarchal component) and curator and art critic Gilad Melzer (on the many ways of “not seeing” of each individual society and on the fact that the largest “blind spot” in Israel is represented by the Arabs).

All texts are in Hebrew, Arabic and English.

A Place of Our Own – Schiltpublishing.com

This review was also possible thanks to the contribution of Cary Benbow.

Aya, exit of student dormitories, Einstein Street, Ramat Aviv. “It’s different to walk here in the center of Tel Aviv with a hijab, than in the neighborhood of Ramat Aviv, I get a lot of attention. I’m used to it by now. I don’t get why it’s so strange for them to see Arab women in the city. Nobody tries to understand and know us. We are motivated by fear, in a society that encourages alienation, which makes it hard for people to approach and make contact.”, – Aya.

View of Tel-Aviv’s rooftops from the roof of Samar’s apartment building, Tel Aviv. “I couldn’t rent an apartment in Ramat Aviv for a long time. When I sent a copy of my ID card, the landlords would suddenly find a reason not to rent me the apartment. <…> Most of the times when the owner sees I’m an Arab, they later tell me on the phone that the apartment has been hired already”, – Samar.

Samar, family plot, Makhoul Village, West Galielee. “This is my mother’s land, inherited from her mother, who lived in the village of Makhoul, on the edge of an Israeli- Jewish community. The officials in Israel do not recognize this land as ours. We are afraid they will want to expand the community and it will harm our land. The area is not connected to electricity or running water, so we water the olive trees in the summer using jerry cans”, – Samar.

Majdoleen, Samar and Saja, mattress, student dormitories, Broshim Center, Ramat Aviv. “The mattress symbolizes for me the alienation and foreignness in this city and the feeling of instability, and even if you live for many years in the same apartment, you will always be reminded that you are a stranger and not always wanted, and be reminded of the struggle to rent an apartment”, – Samar.

Road sign pointing to Nazareth and Kafr Kanna. All the signs on the road, in the streets, and in public institutions, are in Hebrew, English, and Arabic, so members of the Arab population who do not know Hebrew well enough can understand and get along. It may change because of The Nationality Bill, that rules that Arabic is not an official language in Israel, anymore.

Location: Online Type: Book Review, Documentary

Events by Location

Post Categories

Tags

- Abstract

- Alternative process

- Architecture

- Artist Talk

- Biennial

- Black and White

- Book Fair

- Car culture

- charity

- Childhood

- Children

- Cities

- Collaboration

- Cyanotype

- Documentary

- environment

- Event

- Exhibition

- Family

- Fashion

- Festival

- Film Review

- Food

- Friendship

- FStop20th

- Gun Culture

- Italy

- journal

- Landscapes

- Lecture

- love

- Masculinity

- Mental Health

- Museums

- Music

- Nature

- Night

- photomontage

- Podcast

- Portraits

- Prairies

- River

- Still Life

- Street Photography

- Tourism

- UFO

- Wales

- Water

- Zine

Leave a Reply