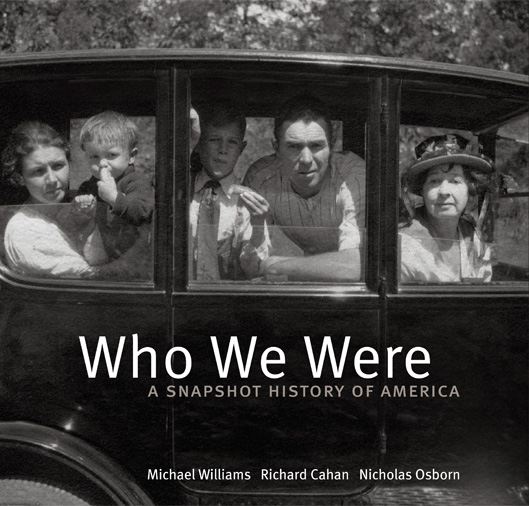

Who We Were: A Snapshot History of America

Michael Williams, Richard Cahan, and Nicholas Osborn

A Review by Erin Paulson

Who We Were is an unconventional history book that chronicles America from the advent of personal cameras in 1888 to the Apollo 16 moon mission in 1972. It contains 350 images compiled over ten years, almost every one with a caption describing the subject, the photographer, or the history surrounding the time period. The book opens with an introductory history of photography, and at first glance the writing seems abrupt and almost elementary, the opposite of the typically obtuse writing styles utilized in most history books. This can be chalked up to the coffee-table book quality one expects with such a large and diverse collection of images. However, if the writing style is at first seemingly jarring or ineffectual, it actually begins to seem almost appropriate and affecting as each progressing page is turned. The preface may not prove especially enlightening to anyone with a basic knowledge of the history of photography, but the straightforward and terse writing style employed by the authors is successful in the introduction for each new section. Brief and to the point, the introductions tell of what Americans were experiencing during that particular time, and how the following snapshots came to reflect their emotions and lives.

The preface also tells of how the authors compiled the snapshots contained within this history, providing the most interesting text of the book. To realize the extent of participation of so many people is actually quite extraordinary. People all over the country were willing to share their family snapshots, as well as snapshots they had collected, with complete strangers. It is testament to the magic of photography to encourage togetherness and trust. The experience of taking a picture and being in front of the camera is inherent in all of us, uniting us with the joy of familiarity, of having a moment captured in time, of recording light in a way that we can remember forever. Many of the photographers were initially anonymous, but through the authors' extensive research, they were able to unearth information about the photographers or subjects for many of the images. It is a thoroughness overwhelming and immediately deserving of appreciation.

The real magic of this book is in the opportunity to view a photographic history of our country where every image is a pleasant surprise never before studied, every page you turn is a discovery, and every snapshot tells the story of the life of the photographer who captured it. It is a humbling and refreshing experience to realize that the majority of Americans are true photographers, capturing what they see not because they have to for artistic or professional reasons, but for no other excuse than their own journaling and enjoyment. Some of the images are full of life, movement, and chance, while others are stiff, posed, and deliberate. Despite the difference every shot is united by the mystery of the person who photographed it, the people photographed, and the recorded moment.

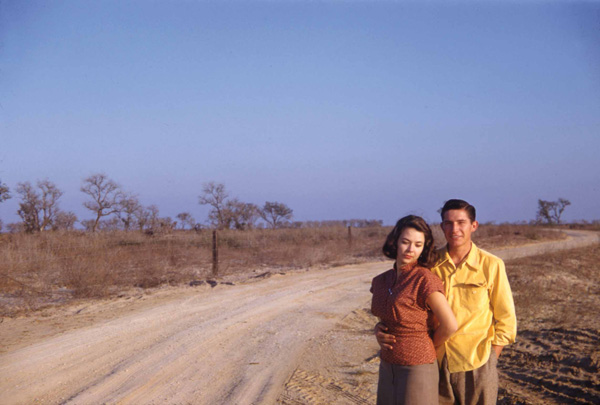

Each of the photographs contained in Who We Were represents its respective time period perfectly, but none so well as the individual portraits. Each portrait enables us to study the face of one who has come before us, to wonder about their life and the lives of those they touched, to witness and share in the memory of one moment in their life. One image that I feel is endlessly evocative is found on page 191 - a striking color snapshot of a young woman with her beau. She stares down demurely, acutely aware of her feminine beauty, while he, with his arm around her, engages the camera. The explanation included by the authors reads, "About 1950 - Falfurrias, Texas. Right out of Tennessee Williams: Doxie Hudson walks along a country road near Falfurrias, Texas, with a long-lost beau. More than a half-century later, Doxie couldn't recall his name, but remembered that he wanted to marry her. He was one of many". This one image with its short caption speaks volumes of the relationships of times past. Doxie seems to represent every one of her female contemporaries in her innocence, potential, and attraction, just as the location seems to represent everywhere in Middle America.

It is amazing that photographs taken by amateurs can call to mind the work of greats such as Henri Cartier-Bresson and Robert Frank. Images where the subject, lighting, and perspective all come together to capture a magnificent scene, such as the one found on page 51. "1918 - Champaign or Urbana, Illinois. Good old Daze: The game of stickball, from a photo album entitled 'My Days at Illinois'". Two young men outdoors in what is reminiscent of the famous University of Illinois Quad, playing amongst the shadows, evokes an overwhelming sense of nostalgia in a simply composed yet beautiful image. These anonymous young men are representative of all collegiate young men of the early twentieth century, just as the aforementioned portrait of Doxie Hudson epitomizes young women of 1950.

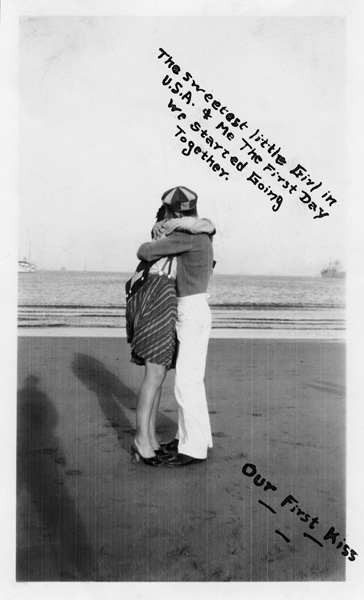

When a portrait is combined with a caption, particularly one written by the photographer or subject, it makes the subjects become even more familiar. An image found on page 131 depicts a young couple in an urgent and honest embrace, with a note written directly on the image: "The sweetest little girl in U.S.A. & me the first day we started going together. Our first kiss". This image creates such a strong desire to share in the rest of the couple's relationship that a deep sense of disappointment occurs upon learning this is the only image of the lovers. That thirst for the complete story is shared with the majority of the portraits found in this history. What happened to these people? Where is the snapshot taken the next day, the next week, the next year?

My favorite images included in Who We Were may be the color photographs shot by amateur Martin Johnson, during the cross-country road trips he would take with his wife, Agnes. The extraordinary thing about them is not their flawless technique, unusual or dramatic subject matter, or the knowledge they provide the viewer. Instead, it is their complete and unyielding simplicity. His photographs captured moments that most photographers would not find shutter-worthy nowadays: a car by the side of the road, a waitress in a dark diner, a water tower in the town of Poplar Bluff, Missouri. Johnson's images record anything and everything he and Agnes witnessed. They are both extremely common and wonderfully unique, and are therefore quintessentially American.

However, not every image compiled in Who We Were reminds us of the innocence of America and its people; some remind us of quite the contrary, and make us thankful that these times have past. Specifically, an image of a large representation of the Ku Klux Klan publicly parading down a busy town street in or near 1922. Such indisputable evidence of the power they held in the South at one time in the history of our country is sickening and disturbing. The inscription describes the Klan's numbers — "The Ku Klux Klan reached its peak in the early 1920s with between 4 and 6 million members" and only furthers the overwhelming disgust one feels at studying the image. However, despite the negative history it demonstrates, it is still part of the story of America and the journey we as a people have taken to reach our current point in time, a theme that carries throughout almost every image found in this collection.

Michael Williams, Richard Cahan, and Nicholas Osborn have accomplished something of significance with Who We Were. Their compilation of images speaks of the course Americans have taken since the advent of photography, and the progress we have made, and continue to make, as a people. Such overwhelming, undeniably honest testaments to who were not only provide a deeper understanding of times past, but also evoke a substantial interest in our own history.

Erin Paulson holds a BFA in photography from Columbia College Chicago. A critic at heart, she has also written film reviews. She currently works as a bookbinder and letterpress printer for LoveLeaf Press. Her website can be found at www.erinpaulson.com