blog

Book Review: On a Wet Bough by Keliy Anderson-Staley

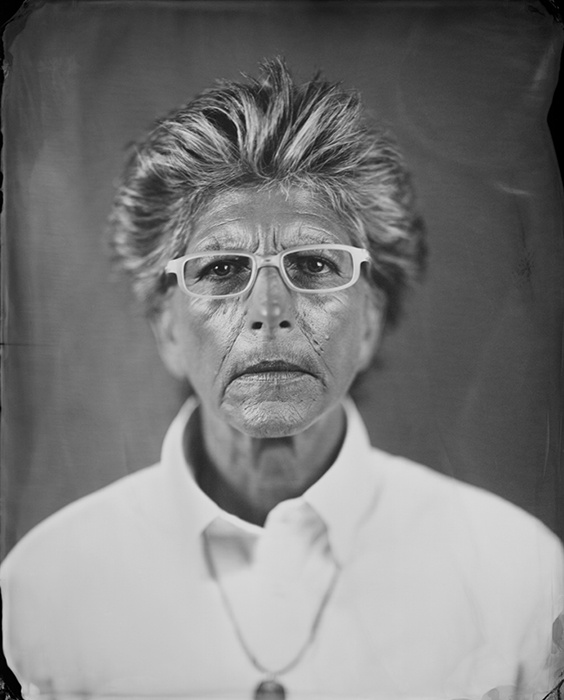

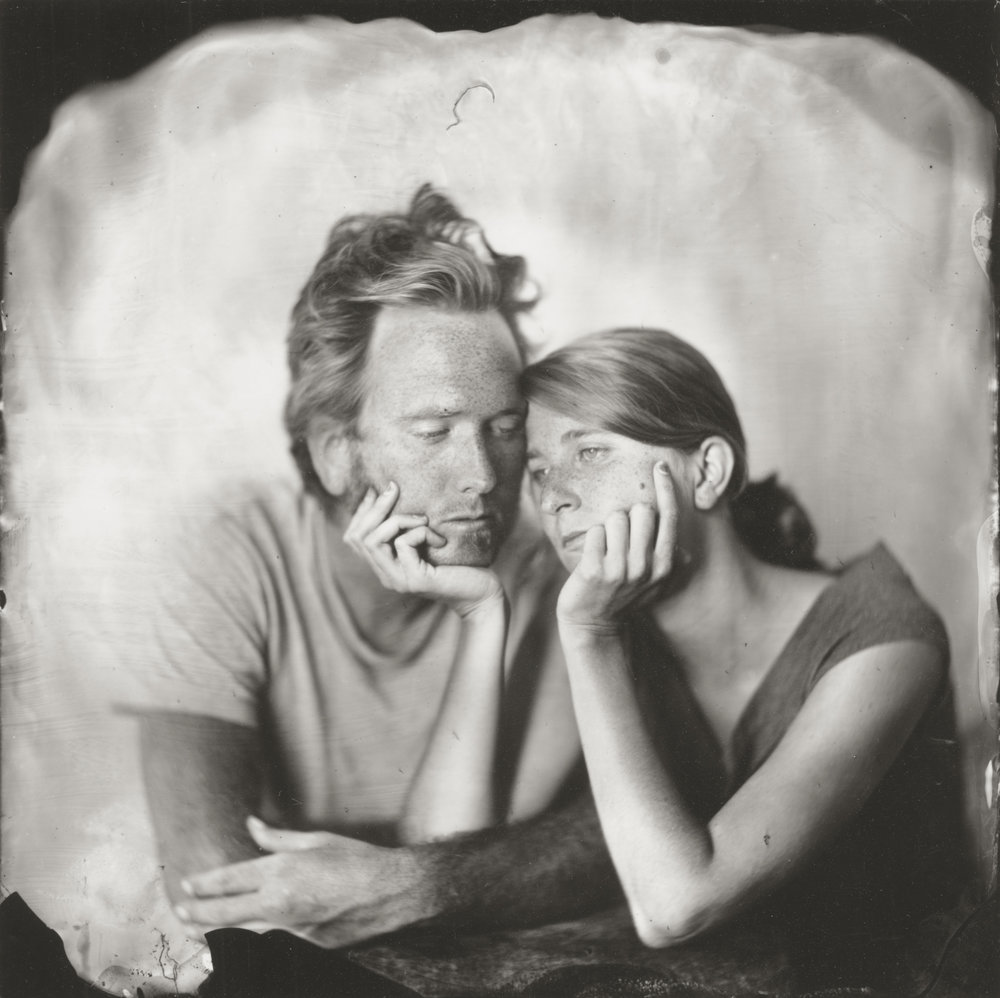

Reine, 2004

The apparition of these faces in a crowd;

Petals on a wet, black bough.

Ezra Pound, “In a Station of the Metro” (1913)

From a 2013 interview between Waltz Books publisher Mary Goodwin and Keliy Anderson-Staley, she said, “I think any portrait can make us think about mortality and transience, but this process—because in a sense it bears an imprint—maybe heightens our sense of time. With these images, actual light strikes the subjects, bounces off of them, passes through the lens, and strikes the liquid emulsion on the plate. Yet these plates are also solid and metal, seemingly permanent. So they can be both a haunting reminder of the passing of time and a sign of our futile attempts to hold on.”

The title of the book, On a Wet Bough, references the Ezra Pound poem In a Station of the Metro. In this quick poem, Pound describes watching faces appear in a metro station. The reader is not clear whether he is writing from the perspective of a passenger on the train or as someone on the platform. The setting is Paris, France, and as he describes the faces as a “crowd,” meaning the station is full of travelers. He compares these faces to “petals on a wet, black bough,” suggesting that on the dark subway platform, the people look like flower petals stuck on a tree branch after a rainy night. This poem is very sensory in nature; it allows the reader to imagine a scene while reading the lines. In the same sense, the portraits Anderson-Staley presents in On a Wet Bough are timeless, yet fleeting in the grand scope of time and humanity.

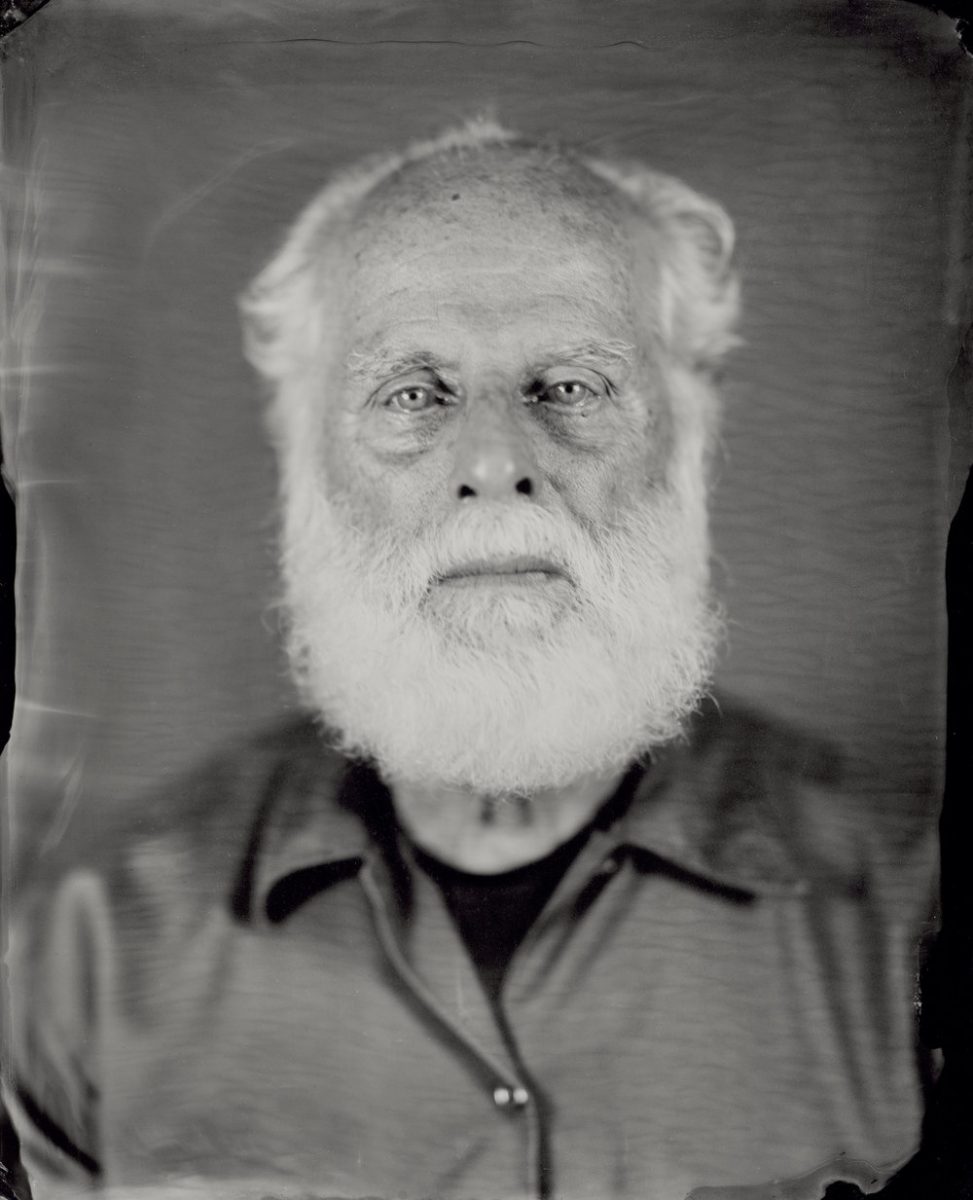

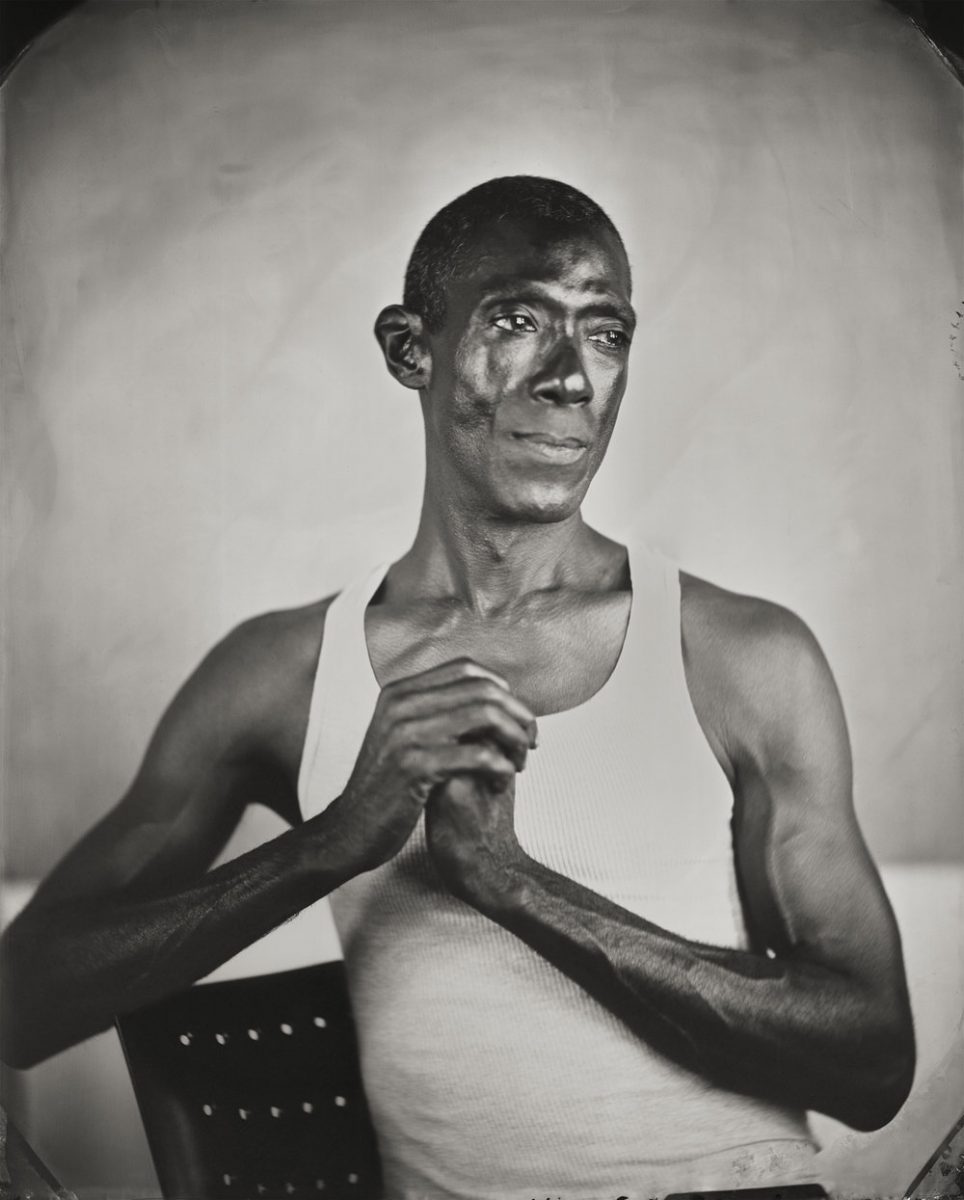

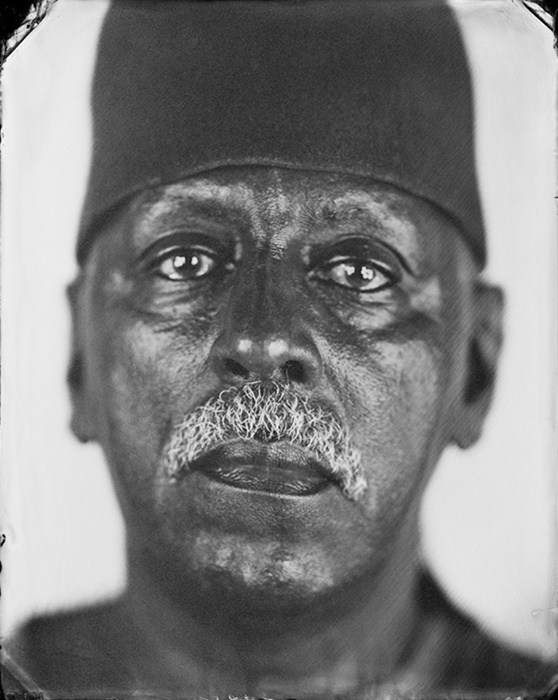

I am drawn to comparison for the ability of the artists to evoke the personality of the sitter. Richard Avedon’s portraits from his book, In The American West, are strikingly different than Anderson-Staley’s, and a technique comparison between the two artists is not on even ground. Avedon uses modern film cameras, white backgrounds, northern-style light, razor sharp focus and intense presentation of details. Anderson-Staley uses a 19th century photographic process, antique lenses, and a image development process which has a multitude of variables that impact the final image. Yet her portraits have an equally powerful punch for the subjects she presents to us. Specific evocative details of the subjects are caught in focus; white hairs grazing a temple, chin whiskers, a nose ring, the catch-lights in a pair of eyeglasses, or the pock-marked skin of an adult which shows the traces of youth that came before. These are the poetic comments made by the camera, drawn forth in the artful craft of processing the plates. The final, tangible photographic image/object is an equivalent to a couple simple lines of poetry which speak volumes and express an intangible attraction which draws the viewer in.

This past year in Indianapolis, I sat to have my portrait made by Keliy. I watched as other portraits were made, and I observed her attentive process to prepare the tintype plates, make the exposure with a subject who must sit still; which commonly takes somewhere in the neighborhood of 10 seconds. This is an eternity compared to the ability of a person to snap and post a photo on Instagram (almost in less time than it takes for Anderson-Staley to make one exposure). Creating a tintype is a beautiful, collaborative process. When I watched the resulting image come into being, I was transported back to first time I ever saw a photographic image developing the darkroom. Pure magic.

In this era of backlit images on a computer screen being the vast majority of the photographic imagery consumed each day, the aspect of the tintype as art object is paramount. One physical quality of Anderson-Staley’s tintypes is the application of a clear top coating that adds a protective layer and, much like a lacquer layer to a painting, it gives depth to the images. There is depth to the images, like when you take a fresh apple from the grocery or market, and rub it on your shirt sleeve, or some of the oils from your hand pass onto the skin. Suddenly there is a depth and shine and a deeper color that wasn’t there before. The skin of the fruit is radiant and glowing. Anderson-Staley’s tintype portraits have the same transformative power. Lustrous blacks and pearl whites are in contrast to each other, and the perfect imperfections of the tintype process infuse a feeling of immediacy.

“At once contemporary and timeless, these portraits raise questions about our place as individuals in history, and the role that photographic technologies and the history of photography have played in defining identity,” writes Anderson-Staley.

Much like Pound, Anderson-Staley connects images of people, much like petals and boughs, to a mass of humanity – linking a scene of humanity with the cycles of nature. Pound’s use of living metaphors adds to the fleeting tone of this poem. Flowers and trees, like human beings on a metro station platform, are constantly moving, growing, and changing. This short glimpse through the metro doors is the only time that group of people will be as they are in that instant. Similarly, the captured slices of time for Anderson-Staley’s subjects (no two petals) will ever look exactly the same again, as rains come and go, time passes, winters freeze, springs thaw, and new buds bloom.

Elizabeth, 2012

Mike, 2012

Kevin, 2010

Erica, 2010

Christian, 2010

Charles, 2011

Jesse and Molly, 2004

Ehssan, 2012

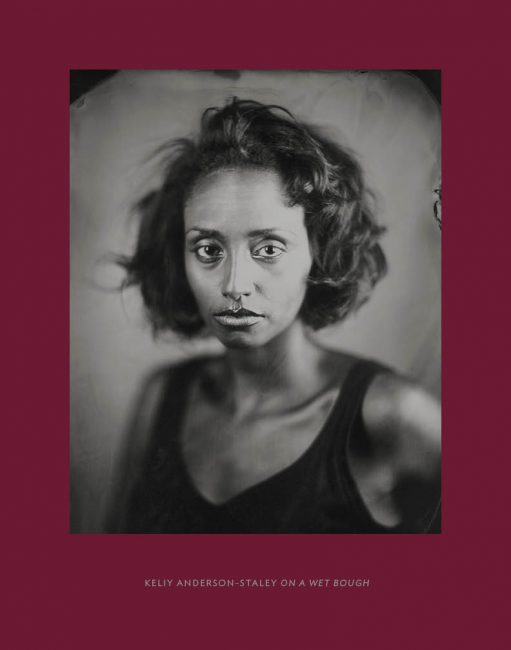

On a Wet Bough by Keliy Anderson-Staley

Essays by Geoffrey Batchen and Matthew Williams

Published by Waltz Books, 2014

11 x 14 inches, Clothbound

144 pages, 85 duotone plates

ISBN 978-1-939932-00-6

Location: Online Type: Black and White, Book Review, Portraits

Events by Location

Post Categories

Tags

- Abstract

- Alternative process

- Architecture

- Artist Talk

- Biennial

- Black and White

- Book Fair

- Car culture

- charity

- Childhood

- Children

- Cities

- Collaboration

- Cyanotype

- Documentary

- environment

- Event

- Exhibition

- Family

- Fashion

- Festival

- Film Review

- Food

- Friendship

- FStop20th

- Gun Culture

- Italy

- journal

- Landscapes

- Lecture

- love

- Masculinity

- Mental Health

- Museums

- Music

- Nature

- Night

- photomontage

- Podcast

- Portraits

- Prairies

- River

- Still Life

- Street Photography

- Tourism

- UFO

- Wales

- Water

- Zine

Leave a Reply