blog

Interview with photographer Eugene Richards

Rte. 42, Twist © Eugene Richards

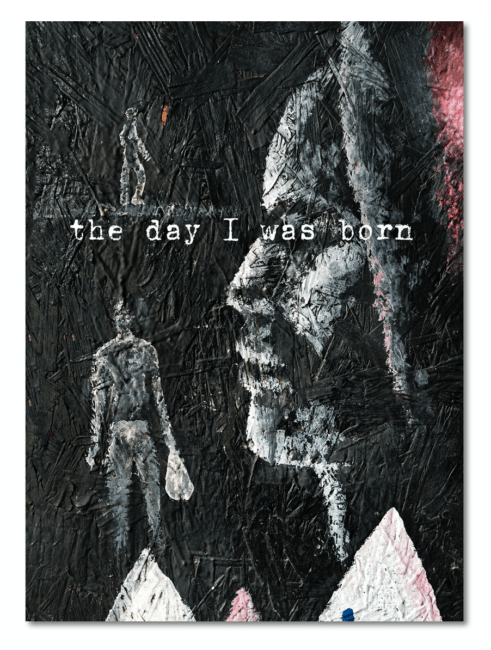

The latest book by Eugene Richards, the day I was born, tells the stories of six men and women who are living out their lives in the memory-laden Mississippi Delta of Arkansas. The photographs were made in and around Earle, Arkansas. The six people are: Joseph Perry, Jr., Stacy Abram, Jackie Greer, Lovell Davis, Jessie Mae Maples, and Timothy Way. Text from each person is pared with Richards’ images, and the resulting book tells the compelling narrative of people whose lives and struggles continue in the decades following events of the civil rights movement in the 1960s-1970s and beyond. Their stories are beautifully captured and poetically told in their own words throughout this book, and Richards is there to listen to their upfront honesty; to compassionately hear their stories, and validate them for who they are. The moving and respectful visual and written slices of life from six people in Earle, Arkansas, and how their truths are shared by so many others, are some of the most important reasons why the day I was born merits our attention.

In our conversation, Richards related his experience in the Delta region of Arkansas in the late 1960s-early 1970s. In 1968, he joined VISTA, Volunteers in Service to America, a government program established as an arm of the so-called “War on Poverty.” Following a year and a half in eastern Arkansas, Richards helped found a social service organization and a community newspaper, Many Voices, which reported on black political action as well as the Ku Klux Klan at that time. “The paper eventually ran out of money and I ended up leaving. The race riots, or that’s what they call them… but if you look it up they weren’t riots… happened in Marianna at the time, but the Delta was a totally ‘voided’ place. You heard about things going on in Mississippi, but very little happening in Arkansas beyond Little Rock with the schools. The Delta was relatively quiet, but the people started to stand up in these little towns,” Richards recalls, “which made a reporter out of me, to work on stories like the local Klan and create the writing and photos… and over the years I’ve gone back periodically to see how its been going. The most recent time was back in 2018 when I met the Joseph Perry, the opening voice in the book.”

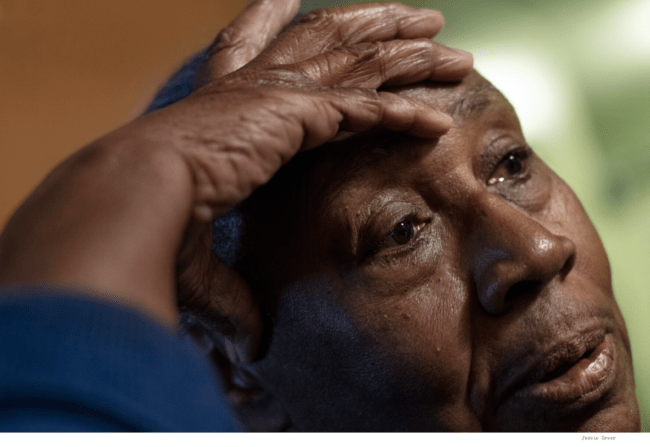

Joseph Perry, Jr. © Eugene Richards

“The day I was born I was black. You went to a black school. You knew that, ’cause you didn’t go to school with no white folk. There weren’t no white teachers, wasn’t no white nothing.” – Joseph Perry, Jr.

It is poignant that Richards uses the word ‘voice’ to describe the role of the people featured in the day I was born. Over the course of our discussion, Richards’ fundamental aspiration was blatantly obvious. He strives to lend a sense of importance to people whose portraits would otherwise, in his words, just be ‘shadows of themselves’ in the context of the larger story. Richards works to validate these people of the Arkansas Delta region by keeping an ideal in mind. “The driving force behind this book, much like the force behind why I started this type of work in the first place during the Vietnam War era, was to create a sense of unity. At that time, Martin Luther King Jr.’s basic call to people was for unity. He said the way to proceed is by unity…and his call for white people to join forces with oppressed people of color. I took that very seriously at the time. And I still do. Maybe today it sounds naive to a lot of people, but nonetheless, that was the driving force.”

Richards recounts how he noticed when he returned on assignment to the Delta there are not any monuments in this area to commemorate the riots and unrest during the civil rights movement, “but I went back to Earle and went down this back street… its actually called Main Street, which is along side the railroad tracks… classic Southern railroad tracks dividing the neighborhoods…and here is this store with all these portraits painted there. That’s how I met Stacy Abram.” The storefront Richards photographed is the building for Abram Heating & Air Conditioning – but it surely could be considered a monument. The prominent faces of numerous black civil rights (one could argue human rights) leaders adorn the facade. MLK Jr., Malcolm X, Marcus Garvey, Harriet Tubman, Angela Davis, John Brown, Barack Obama, and a black Jesus are among the faces that Stacy Abram says he “wanted to enlighten people, bring them up out of the darkness. Show them they wasn’t just born into he way it is now.”

Abram Heating & Air Conditioning © Eugene Richards

black Jesus © Eugene Richards

During our talk, Richards empathically recounts how meeting the folks in this book came as a natural progression. One person lead to the next and Richards speaks of the six individuals as people he holds in close regard; people who have invited him into their lives, their homes, and have slowly revealed themselves and their truths. After working the project and shooting photos in and around Earle, doing interviews and returning to New York with the work, he says, “I came back, turned in my pictures, and an editor at the (New York) Times said there was a story there. I suspect that what caught hold at that time was the not-so-nascent movement asking the broad question: ‘who is the right person to tell the story’. The 1619 project was in full bloom at the time, and I met with a group of editors around a table at the Times later to show the work, and no one said a word. I went home after that meeting and I never heard from them again. I knew there was a story there… any one of these people could be a story,” Richards shares. “So what do you do? I had all these interviews… and wanted to do a book… but COVID came along and I couldn’t go back to do more work… so we, my wife Janine and I, ended up deciding to self-publish the book in the way I wanted to do it.” Richards also wonders if he naively thought he was the right person to tell the story in the end. Considering his background and history with that part of the country, and that the story has been taking shape and been happening since Richards initially time spent in the Delta, I say nobody is better suited than he to return and continue to tell the story.

“It’s not only this town, it’s the world. It’s not just this town, it’s the complete world.” – Lovell Davis

2nd Street, Earle © Eugene Richards

I asked Richards if he felt like his role of telling these stories could be perceived as that of an ‘outsider’ – despite his decades of direct experience covering issues of race and and stories involving of people in need. He replies, “It’s often seen as derogatory to be the outsider when working on things like this, but I don’t find it derogatory. As a journalist, reporter, writer, photographer, reviewer… whatever we are… we are outsiders. That’s what we are. And as painful as it is, you come, you build relationships and you leave.” I also asked if it’s difficult for him to start and stop working on stories involving people in need. “It’s never, ever satisfying. It sounds terrible, but there is always the sense that nothing is ever finished,” he says. “You start and stop working on things, and sometimes leaving the story is extremely painful. Sometimes the story stays with you, and despite all you’ve done it feels like it gets diminished.”

The rush and immediacy of a meaningful story, a movement, or a reckoning with our societal past and culture has gravitas. It often has a sense of importance and momentum. The concern about a ‘diminished feeling’ is what many people have felt in America in 2021 after the groundswell of urgency and attention of the Black Lives Matter movement in 2020. Richards book, the day I was born, is extremely important to refocus our collective attention. His work in Earle – the voices of people, the photographs and the sense of place he captures, is expertly informed by his efforts over the years to highlight the lives of underrepresented people. Richards is a humanist in this way. He has not lost his drive to build relationships, advocate for others, and tell their stories in a truly lyrical way that is often all but forgotten in much of contemporary photojournalism.

Jackie Greer © Eugene Richards

farm work, Marianna © Eugene Richards

Timothy Way © Eugene Richards

Nina and her grandson © Eugene Richards

blackbirds towards evening © Eugene Richards

the day I was born

by Eugene Richards

Many Voices Press, © 2020

Photographs and Interviews by Eugene Richards

Paintings by Timothy Way

Eugene Richards was born in Dorchester, Massachusetts. During the 1960s, Richards was a civil rights activist and VISTA (Volunteers in Service to America) volunteer. After receiving a BA in English from Northeastern University, his graduate studies at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology were supervised by photographer Minor White. Richards has published many volumes of photography on such diverse subject matters as poverty in America, women’s breast cancer, the aftermath of 9/11, emergency medicine and the lives of veterans of the Iraq war. He has been a member of Magnum Photos and of VII Photo Agency. To learn more, and purchase a copy of the day I was born, visit his website at https://eugenerichards.com

Events by Location

Post Categories

Tags

- Abstract

- Alternative process

- Architecture

- Artist Talk

- Biennial

- Black and White

- Book Fair

- Car culture

- charity

- Childhood

- Children

- Cities

- Collaboration

- Cyanotype

- Documentary

- environment

- Event

- Exhibition

- Family

- Fashion

- Festival

- Film Review

- Food

- Friendship

- FStop20th

- Gun Culture

- Italy

- journal

- Landscapes

- Lecture

- love

- Masculinity

- Mental Health

- Museums

- Music

- Nature

- Night

- photomontage

- Podcast

- Portraits

- Prairies

- River

- Still Life

- Street Photography

- Tourism

- UFO

- Wales

- Water

- Zine

Leave a Reply