blog

Interview with photographer André Ramos-Woodard

me?, 2020 © André Ramos-Woodard

While reviewing the work online for André Ramos-Woodard’s portfolio in Issue #116, I recalled hearing them speak about their work on the podcast Keep the Channel Open. André’s frankness and upfront honesty struck me in a very positive way. They talked about the importance of reaching a Black audience through their work in part because their creative practice is a way to gain a greater understanding of Self, and all the layers which make up what it is like to be queer and Black. They also spoke specifically about reaching people who are a very important component in his work; family. “We love each other and we are undeniably Black.” Ramos-Woodard also spoke about the process of educating others and talking about their positive life experiences of Blackness, how to hone in on it, how to love it. How to fight against white supremacy, and try to reconcile with it. Through Ramos-Woodard’s work, the discussion becomes open for all people to learn, listen, and search for understanding.

Cary Benbow (CB): Why do you photograph? What compels you to make the images you create?

André Ramos-Woodard (ARW): We gettin’ right to it!! Haha, well, I think I photograph both because I like to and because I’m really comfortable doing so. I started looking at images a bunch when I was in high school, and from there I decided to get my undergrad and grad degree in photography. I guess I’ve just spent a lot of time with the medium.

As far as the images I create… hmm, for the most part, I use my images (and image-based artworks) to get my thoughts and feelings out. Making things helps me confront things, whether it be personal feelings, societal issues, or cultural celebration.

CB: Why did you become a photographer, and who are your primary influences who inform your creative practice?

ARW: To be honest, I became a photographer because I was really compelled to learn how to recreate the images and photo montages I was seeing in high school. There was an assignment I had to do in my photography class where I had to look through some images on Flickr. I don’t even remember the complete details of the assignment—I just remember getting absolutely lost in pictures. After that, I would literally spend hours every day just looking at different images on the internet.

My primary influences are my friends and family, but if we’re talking about artists, that’s hard… right now would probably be Qualeasha Wood, David Leggett, Mike Q, Kerr Cirilo, and Christopher Troutman.

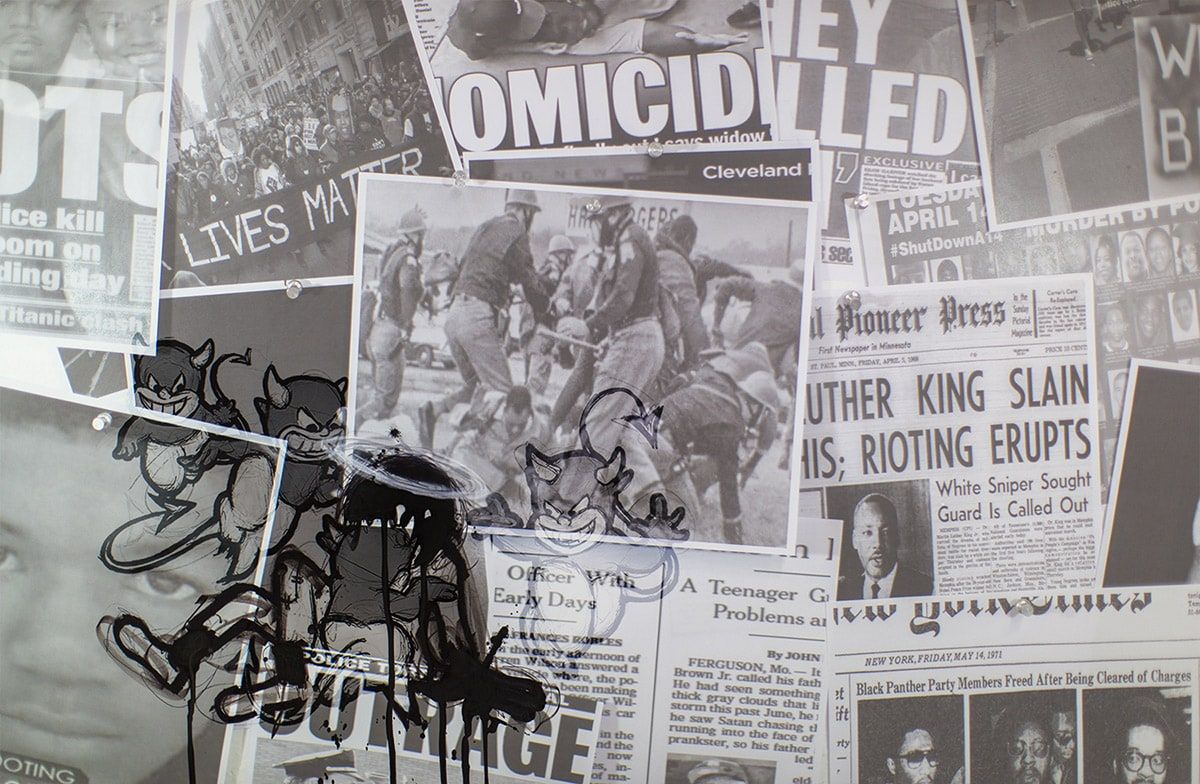

news, 2020 © André Ramos-Woodard

melodrama, 2021 © André Ramos-Woodard

CB: What was your start into photography?

ARW: It was when I was in high school. I moved from Goodlettsville, TN to Beaumont, TX right after the school year started. Since I was a little late, when I went to sign up for classes, Art was already full. It was a choice between photography and gym, so I chose the more creative option.

If you wanna get really technical, I remember asking my mom for this purple dinosaur camera from K-Mart when I was like nine. I got the photos developed and thought it was cool… then went back to playing Kingdom Hearts LOL.

CB: What inspires your art? What kind of stories do you wish to tell?

ARW: Aesthetically, I’m still inspired by a lot of the visuals I was attracted to growing up: anime and cartoons, video games, TCGs like Yu-Gi-Oh! and Pokémon. Even though these mediums aren’t fields of choice in art school per se, the expansiveness and creativity I find in that stuff never seems to let me down.

The stories I portray are from my experience. As a queer Black person, I want to assist in the dismantling of the problematic systems in place—both inside and outside of the art world—that repress “othered” people. I hope to talk about the realities of what I have to deal with as a person who belongs to marginalized communities while simultaneously celebrating them.

CB: What do you wish the readers take away from your project?

ARW: Well, BLACK SNAFU is all about reclaiming this visual language that was used in a detrimental way against Black people in order to call attention to the historic and contemporary ways that white supremacy has plagued American history (at the very least). I want readers to understand that just because some of these racist caricatures have been banned from reappearing in cartooning doesn’t mean that we’ve forgotten about them; they’ve perpetuated too much of their harmful ideologies into our culture. It’s like how just because a country passed some laws to make racism socially unjust doesn’t eradicate racism from its citizens.

That being said, I also want readers to understand that Black people have been, continue to, and always will fight back against a system that does us wrong. We will continue to celebrate our existence!

CB: Your work includes many different visual elements and/or themes which are non-lens based — is photography your primary choice of expression?

ARW: Yep, photography is my primary method of expression, whether I like it or not! I consider myself more of a photo-based artist rather than a photographer since my practice combines photography, text, drawing, collage, and installation. Still, I just can’t seem to get away from photography! Even though I did go through a phase in grad school where I was pretty fed up with thinking so critically about the medium and only made drawings for an entire semester, I can’t really imagine a day where I could give up photography. Maybe it’s simply because it’s the easiest language for me to interpret since I’ve spent so much time with it, or maybe it has something to do with the ways that photography can depict (or pretend to depict) our reality in comparison to so many other artist mediums… who knows.

buds, 2020 © André Ramos-Woodard

BLING, 2020 © André Ramos-Woodard

CB: Can you please explain the idea behind your images submitted to this issue? How do they relate to your other projects, or are they significantly different?

ARW: The images I submitted to this issue are currently my favs from the series BLACK SNAFU since it’s still a body of work that is in development. I think I work normally from a diaristic point of view, so this body of work is a bit more urgent than my normal stuff if that makes sense. I have an older project called a mediocre-ass nigga and a newer one called NOTE TO SELF(s) that both primarily explore my personal experience with mental health. But, as a Black queer male-modied individual, facets of my identity inevitably come through in the work. As a Black artist, BLACK SNAFU is in dialogue with all of the self-reflective works that I make.

When I started BLACK SNAFU back in 2020, I specifically wanted to create photographs that were more celebratory in contrast with the vile caricatures I was ripping from cartoon history. I went into it thinking that if I made positive images, it would fight against the treachery caused by minstrelsy. It didn’t completely work and I eventually got tired of looking at minstrels, so I started adding pro-Black characters in my images, like Huey from The Boondocks and Oscar Proud from The Proud Family. To me it feels like a big battle between good and evil sometimes. Ya know, like the pro-Black ideologies trying to beat up and reclaim the identity that is rightfully theirs!

CB: What do you feel are the ‘obligations’ of an artist addressing human rights issues?

ARW: Well, I think it’s up to the artist to do what is right by the people being depicted in the pieces. For example, I want to ensure that I do not harm the ways that Black people are viewed in a society that already cuts us down by making the work that I make. Though I am Black, I do not and cannot speak for an entire community. It’s up to me to talk to other Black people about how they interpret the work, what it says to them, and learn how I can better help our collective voice be expressed.

And if I were to make work about a community that is not my own, I damn sure better be on my toes. If someone can’t speak to an experience, I question their authority to even cover those sorts of issues. That being said, I recognize that people in positions of power and privilege can really amplify unheard voices. We need those artists to do their research and use their powers specifically for the people.

authenticity (2 CHAINZ) © André Ramos-Woodard

sting, 2020 © André Ramos-Woodard

CB: Who are the people that appear in your photographs? Are they more important than just being a figure in the image?

ARW: Ah, this is something I have been thinking about a lot recently, so I appreciate your question. Most of the work is self-portraiture, so usually the people that appear in this body of work are me. Actually, the only image in this portfolio that doesn’t contain an image of me is authenticity (2 CHAINZ), of which is my Mama’s hands.

I do this because I recognize the fact that reclaiming these minstrel caricatures in my work means something. After all, a lot of the characters in this series are racist. They have done harm to my people. It isn’t just purely a visual thing for me when I place myself in created spaces with these characters, so I’m cautious about using other people in work that is so visually charged. I’ve been thinking more proactively about celebration though, so I’ve started to include my family in images that I consider to be overtly positive.

CB: What advice would you give to someone who wants to take on projects like yours?

ARW: Yo, go for it and have fun, but be thorough as you learn! Be diligent with your research. I am still learning a lot about the history of American minstrelsy, and as this project progresses, I want to ensure that I do Black people right by learning as much as I can. There’s plenty of artists and cartoonists within the realm of Black American history that I’ve yet to investigate, but I’ll get to them since I want to really speak to the expansiveness and importance of Black American history.

Also, please take breaks. Making work that has to do with themes of discrimination and marginalization can be extremely exhausting, especially for people that are part of the marginalized communities themselves. There’s nothing wrong with taking a day, or a week, or a month off from doing the work to get away from some of the trauma. Work like this may be important, but so is mental health!

Air Gerald (BOOMSHAKALAKA-ON-EM) 2021 © André Ramos-Woodard

::

Raised in the Southern states of Tennessee and Texas, André Ramos-Woodard (they/them/he/him) is a contemporary artist who uses their work to emphasize the experiences of the underrepresented: celebrating the experience of marginalized peoples while accenting the repercussions of contemporary and historical discrimination. Working in a variety of media—including photography, text, and illustration—Ramos-Woodard creates collages that convey ideas of communal and personal identity, influenced by their direct experience with life as a queer African American. Focusing on Black liberation, queer justice, and the reality of mental health, Ramos-Woodard works to amplify repressed voices and bring power to the people. Their work was just awarded the Carol Crow Fellowship award from the Houston Center for Photography, where their work is on exhibition for the 2022 Annual Fellows.

Location: Online Type: Featured Photographer, Interview

Events by Location

Post Categories

Tags

- Abstract

- Alternative process

- Architecture

- Artist Talk

- Biennial

- Black and White

- Book Fair

- Car culture

- charity

- Childhood

- Children

- Cities

- Collaboration

- Cyanotype

- Documentary

- environment

- Event

- Exhibition

- Family

- Fashion

- Festival

- Film Review

- Food

- Friendship

- FStop20th

- Gun Culture

- journal

- Landscapes

- Lecture

- love

- Masculinity

- Mental Health

- Museums

- Music

- Nature

- Night

- photomontage

- Podcast

- Portraits

- Prairies

- River

- Still Life

- Street Photography

- Tourism

- UFO

- Wales

- Water

- Zine

Leave a Reply