blog

Interview with photographer Rick van der Klooster

From ‘The Day the Birds stopped Singing’ © Rick van der Klooster

The featured photographer for ‘Issue 114 – The Portrait 2022’ is Netherlands-based artist Rick van der Klooster. For this issue, contributors were prompted by: What makes a portrait a portrait? How is it different from a snapshot, still life or a landscape? Do we learn who a person is from a portrait or do we learn more about the photographer? In my conversation with Rick van der Klooster, we try to address some of these topics and more.

Cary Benbow (CB): Why do you photograph? What compels you to make the images you create?

Rick van der Klooster (RK): I think photography is all about expressing my feelings, thoughts and ideas I have about the world as I experience it. Normally I am working on long term projects that easily take more than two years to complete. Sometimes I won’t photograph for a month and it still feels alright, as long as I know I’ll be able to pick up my camera when I want.

The work I make originates mostly from an urge to visualize something I think a lot about, but can’t put into words as I would like to. Then I try to find a visual subject that can translate these thoughts into metaphors that form a story or a photographic world to read.

For example, my project The Day the Birds stopped Singing started with a walk to the local supermarket. It was just before the covid pandemic hit and I was in my graduation year. The thought of becoming fully responsible for my rent, taxes, food, healthcare, etc. scared the hell out of me. During the same period I was also reading a lot about the huge wildfires in Australia – and the combination of thinking about my own future that involved a lot of financial and bureaucratic stuff while the future of the world is so damn precarious made me wonder why I should worry about taxes while the world is literally burning. While my head was filled with these thoughts, I walked down the stairs to go to the supermarket when I saw this little gray pigeon looking up. She hopped up the stairs while I descended, and I had to laugh at the sight of a winged animal deciding to take the stairs. Of course, she immediately flew away at the sound of my laugh. This seemingly banal encounter was an important moment for the start of my project.

This idea of having wings and the ability to go anywhere you want reminded me of this saying I’ve heard so many times from older people. ‘You’re so young! The whole world lies open for you, you can go everywhere you want.’ Same could be said for the birds in the city, right? Why would you live in a concrete, car-filled city if you could just fly away? Much like most of my peers these birds are forced to live in cities, because their homes can’t provide for the future. What use are our wings if there is nowhere to land?

So this walk to the supermarket, the thoughts I was having and the short encounter with this little pigeon made something click. And I think this is what compels me to take photographs. There is something about photography that makes me see my environment in a different way; there are so many subjects that could acquire a new meaning in the process of photographing and editing. And as a result I hope to translate my own feelings and thoughts through these subjects into something bigger, so that other people can relate and reflect on it as well.

From ‘The Day the Birds stopped Singing’ © Rick van der Klooster

From ‘The Day the Birds stopped Singing’ © Rick van der Klooster

CB: What inspires your art? What kind of stories do you wish to tell?

RK: To be honest I think it all starts with aesthetics. That is what made me interested in photography in the beginning, just the way it can look. This whole idea of pointing a machine in front of me, pressing a button and capturing something I (want to) see is magical to me. During my studies I discovered how this act of capturing my environment can be a way to translate the things in my head into images that can be read by other people. So now I focus mostly on finding ways to do just that. I think photography is a wonderful medium to restructure the way we look at our surroundings. The world got so much richer since I first picked up a camera and I met so many wonderful people through photography.

I mostly make work about transience, this is inspired by the early deaths of my parents of course. But it is also something that I think is really important to be aware of. It is so easy to get lost in the daily grind of everyday life and for me it is vital to think about how easy it can all go away. It makes me focus on the things that I think are important to me and that’s exactly what I try to convey in my work. To make photographic worlds and the stories within that tell something about transience and memory. In my work the landscape and its inhabitants transform into metaphors about the underlying themes.

CB: What or who are your photography inspirations – and why?

RK: There are a lot of photographers that I really admire and inspire me. Some inspire me in the way they are working, others mostly aesthetically wise and a few in the combination of those two. In my first year of the academy Awoiska van der Molen really inspired me to review black and white landscapes and how darkness can make a photograph more magical and captivating. Saul Leiter really taught me a lot about the beauty of photography without all the ego stuff surrounding it; exhibitions, prizes, money etc. In my third year I did my internship with Jaap Scheeren and he really thought me how to be honest in my artistic practice. He also helped me a great deal with developing my own way of photographing and how a flash, staging situations and portraits can contribute to this.

Lately I have been looking a lot at the work of Raymond Meeks, Bryan Schutmaat, Jenya Fridlyand, Boris Snauwaert, Wouter van der Voorde – and since last week the work of Tim Carpenter who I met at the Ragusa Photofestival. There is something about their body of work that really captivates me. I think there is a magical aspect to the way they capture the world. They aren’t “easy” photographs in my opinion. It’s beautiful how they transform everyday scenes into something deeper that you can read and reflect on.

CB: As I’m viewing the images you submitted for the new issue, I want to ask how you originally considered them… Your portraits from ‘The Day the Birds stopped Singing’ and ‘A Conversation between the Mountain and the River’ are related directly to the themes of the projects, yet they also work well apart from the projects as well. Do you feel the same way? In the end, are the images more about the person shown, or more about the larger narrative of the project? Or both?

RK: Interesting question! I’ve never really thought about how the portraits work apart from the project they belong to. It is the body of work that makes the individual photographs work for me. However sometimes a portrait and/or the act of photographing someone inspires me to make new photographs or even a new project.

Until now it was never about the person shown in the photograph, it sounds a bit harsh, but they function purely as a metaphor for the underlying themes. Of course I choose them for who they are or how they look, but only to translate something from my head into something visual. I’ve found that using portraits of people in my work really helps with conveying an emotion that I found harder to do with a photograph of a tree, rock or pigeon. With that said, I think putting a photograph of a person between photographs of trees, rocks and pigeons helps with creating a photographic world where a photo of a rock could say as much, or even more, than a photo of a human being. In the end they all have to work together to translate the themes into a visual plane.

From ‘The Day the Birds stopped Singing’ © Rick van der Klooster

From ‘The Day the Birds stopped Singing’ © Rick van der Klooster

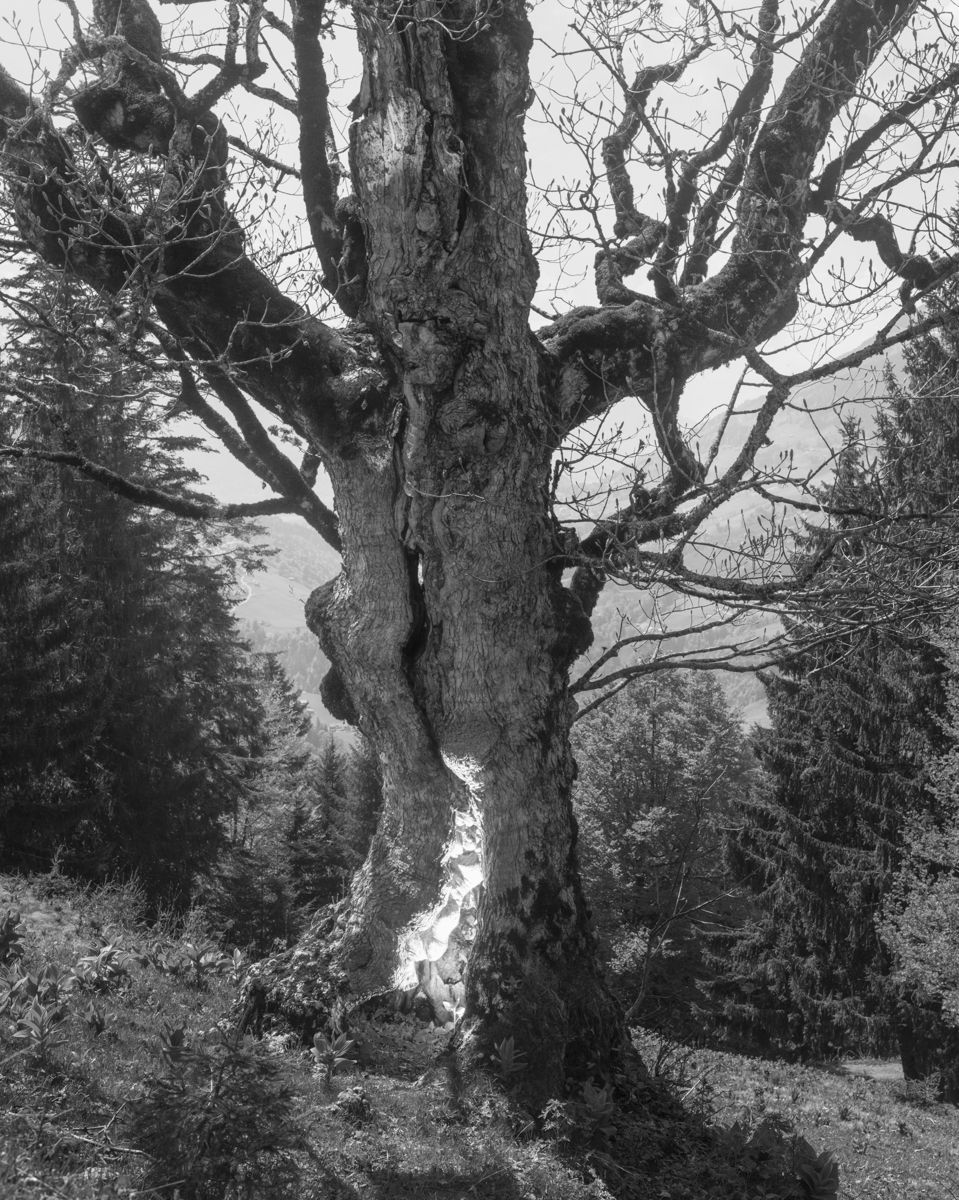

From ‘A Conversation between the Mountain and the River’ © Rick van der Klooster

CB: I read your statement about ‘A Conversation between the Mountain and the River’, and the connection you made with nature and the influence of your mother. In this way, the work translates into a precious remembrance and a way to honor your mother. This project is a wonderful, beautiful exploration of family, sense of self, and how all of us are connected to our surroundings. Is there more you want to add to this, or discuss about the work with these ideas in mind?

RK: In A Conversation between the Mountain and the River I use a landscape that means a lot to me. Something I’ve been thinking about last year is the landscape itself and how magical it is that a landscape can be more than something that is pleasing to the eye or the material resources it has. For me, this landscape keeps my mother alive in a way – without this landscape she would really die. It feels like this landscape absorbed memories that I’ve forgotten myself. So I’ve been thinking about natural conservation a lot, because it isn’t an exaggeration to think that this landscape could be destroyed if it could be profitable for a big company. A good friend of mine who grew up in China saw his natural surroundings disappear over time and with that his feeling of home disappeared.

So the underlying theme of transience in this project is as much about my mother as about the landscape itself. A landscape is way more than its visual and material existence, in a way it can also give you back what you’ve lost.

CB: Are the people who appear in your images more important than just being a figure in the landscape?

RK: I work with small apertures so that I can show the background as sharp as well as the person portrayed. It’s really important for me to find a fitting background because it helps with the narrative and/or feeling of the photograph itself. So most people in the photographs are friends and sometimes I’ve been lucky to find a stranger in the right place, with the right lighting. But mostly it’s a slow process that requires patience from others. Finding the right person, location, lighting and sometimes props takes time and I’ve found out that working together with the person being portrayed helps with making a better portrait than figuring everything out myself. I’ve heard some people say that my portraits are documentations of a small performance. I like that idea, that the portrait is a collaboration between the photographer, the person portrayed and the landscape itself.

But to answer the question plainly – they’re exactly what you’ve said; a figure in the landscape. I think that is their strength within my portraits, the people are part of the landscape they’re portrayed in. For me it’s more about the way they’re standing, looking or what they’re doing than who they are themselves. I try to direct their posture and movements, but it happens frequently that the photograph I publish is the one I took after I said “Okay! We’re done!”. There is a brief moment of relief after standing for the camera for a while and I always press the shutter one more time at that moment.

CB: Does the COVID-19 pandemic change the way you view these projects or images made beforehand or during the pandemic now?

RK: I think they actually formed the projects and images in a way. I’ve started ‘The Day the Birds stopped Singing’ two weeks before the pandemic and I’ve been working on ‘A Conversation between the Mountain and the River’ since 2018. However I’ve decided to not include the images made before the pandemic. For me the world really changed when the Netherlands went into the first lockdown and the academy closed.

The Day the Birds stopped Singing started just two weeks before the first lockdowns. It wasn’t made with COVID in mind. But the pandemic definitely shaped this project, as it reshaped me and my artistic practice. I don’t think I speak just for myself when I say the lockdowns really forced us to reflect on ourselves and our surroundings. Personally I was kind of relieved that suddenly everyone around me was thinking about their transience and vulnerability. Because I lost both my parents before I was 19 years old, I always knew that life is not forever and how easy things can fall apart. And I could feel very alone in that, but all of the sudden everyone was aware of our fragility and it was a large topic of conversation for a while. It felt comforting to know that I wasn’t alone anymore in being constantly aware of how fragile life is.

This really helped me realize that most work I made was always about transience in a way, as if my unconsciousness tried to tell me something through the lens, but I didn’t see it myself. After that realization it made it also easier to know what to look for, to find the subjects that could tell something about themes like transience, precariousness and vulnerability.

From ‘A Conversation between the Mountain and the River’ © Rick van der Klooster

From ‘A Conversation between the Mountain and the River’ © Rick van der Klooster

From ‘A Conversation between the Mountain and the River’ © Rick van der Klooster

CB: For the book project ‘The Day the Birds stopped Singing’, you include elements of wildlife, landscape, man’s inclusion/interaction with nature. Please comment on why you choose to depict these elements in the way you did.

RK: In short the project is about growing up in a dying world. It totally revolves around this liminal feeling where we know everything changed, but it isn’t visible yet. My local city park poses as a backdrop for the project; a man-made landscape, designed to look as natural as it can be. But through the branches a tall, sterile white hospital is visible, cars are parked all around the park and loud restaurants are just hidden from sight. The birds that fled to the park, away from their destroyed habitats, sit on the same branches that obscure the fact we’re actually standing in the middle of a concrete, car-filled city. Under these branches me and my peers sit together, smoking a cigarette and talking about how we wished there would be clean water so we could swim in our own city.

This local park forms a perfect metaphor for the state of nature, humanity uses it as a profitable object, something you can extract from, reshape and brand as something that you can consume. Most photographs in the book were taken in this small park, with the use of a flash and black-and-white photographs, I stripped the park of its natural light and colors and reshaped it into an ominous decor where the local city birds and my peers are portrayed.

The portraits, the way we edited and the title of the project creates a narrative about this liminal feeling me and many of my peers experience.

CB: What do you wish the readers to take away from your project/book?

RK: To be honest with you, I didn’t really think about this during the photography stage of the project. ‘The Day the Birds stopped Singing’ started out as a way of venting my anger against the way we treat the earth. I postponed my graduation after 4 weeks of online lessons, so I didn’t have a teacher ask me this question every day of the week, which probably helped with no thinking about what the reader could take away from the project.

But in the end, when I started editing together with Matthias Batzli, I thought the project should create a small photographic world where the reader can move freely, but within the border of the theme of the project. It’s not that I want someone to put down the book and think:”Ah, I get it!”. I rather want to make the reader feel something, to reflect on what they see and think about what they feel.

When I exhibited the project and book during the ‘Steenbergen Stipendium’ in the Dutch Photography museum in Rotterdam there was a small contest where people could leave a voting ballot and write their reaction on it. After the contest the curator gave us all the ballots with something written on it. One of them was from a teenager who said she was really happy there was something in a museum that was about how she felt about the future. I was extremely happy to read that someone felt heard by the work. Of course there are certain things I hope people take away from the book, but the most beautiful thing is when people engage emotionally with the work and the theme behind it and find something between the covers of the book that I didn’t know was in there.

CB: Let’s talk about the role of a photographer as “publisher” and what you think about the recent increased push for photographers to publish photo books.

RK: During the academy I only made books as projects, to the annoyance of some teachers who say the photo book market is dead. But I guess I just like to make books and I like to read them, no matter if it’s profitable or not.

While self-publishing a book you could get lost in all the freedom you have. I see friends end up photographing, editing, writing, designing and printing the book themselves. Which could be fun, but I think when you feel the need to publish your work as a book the best part is to find people to work with, that is where the book gets so much richer in my opinion. For me it was a revelation to work together with an editor. Seeing someone go at it with only my photos and a small text I’ve written about what I want to show with the book was an amazing experience.

Just last week at the Ragusa Photofestival I was attending a talk about photo books and the artist said something about wanting an abbreviation of the title on the spine of the book, but the publisher turned the idea down because it wouldn’t be smart commercially wise. And that’s something interesting about self-publishing, because I see a lot of people start a crowdfund or pre-order and only start printing the book when the funds to cover the printing costs are in their bank account. In that way you could do whatever you’d like, because if you’re not doing it to turn a profit then you could do whatever you want with your own team as long as you can get the funds to produce the book.

But after self-publishing my graduation project I would like to experience the process of making a book with an established publisher. Having only published one book and zine myself I feel the need to try out something new and to learn more about the publishing aspect of photo books.

CB: What work are you currently working on? Any new projects?

RK: At the moment I am fully focused on my long term project A Conversation between the Mountain and the River. Because the project takes place in Austria, there are gaps in the process that are mostly filled up with thinking, writing and editing photos. I am going back to take new pictures in September. It feels like the project is coming to an end after five years, and it’s going to be a photo book for sure. I also want to experiment with the exhibition; projections and sound are something which could be fitting for the project.

::

Rick van der Klooster is a freelance photographer currently based in the Netherlands. His photo book, The Day the Birds stopped Singing was first published in 2021. For more information, and to see other projects, visit his website www.rickvanderklooster.com , or Instagram www.instagram.com/rickvanderklooster/

Location: Online Type: Black and White, Featured Photographer, Interview, Landscapes, Portraits

Events by Location

Post Categories

Tags

- Abstract

- Alternative process

- Architecture

- Archives

- Artist residency

- Artist Talk

- Biennial

- Black and White

- Book Fair

- Car culture

- Charity

- Childhood

- Children

- Cities

- Collaboration

- Community

- Cyanotype

- Documentary

- Environment

- Event

- Exhibition

- Faith

- Family

- Fashion

- Festival

- Film Review

- Food

- Friendship

- FStop20th

- Gender

- Gun Culture

- Habitat

- home

- journal

- Landscapes

- Lecture

- Love

- Masculinity

- Mental Health

- Migration

- Museums

- Music

- Nature

- Night

- nuclear

- Photomontage

- Plants

- Podcast

- Portraits

- Prairies

- Religion

- River

- Still Life

- Street Photography

- Tourism

- UFO

- Water

- Zine

Leave a Reply