blog

20th Anniversary Issue: Allison Grant

As part of F-Stop Magazine’s 20th anniversary celebration we invited past featured photographers to share with us some thoughts and reflections. We asked each photographer to consider how their photographic work has changed over time, how the changes in photography over the past 20 years may have affected or influenced that change, and to share what they are up to most recently.

By Allison Grant www.allisongrant.com and Kariann Fuqua www.kariannfuqua.com

Allison Grant, In the Wisteria, 2019, Inkjet photograph, 48 x 36 inches

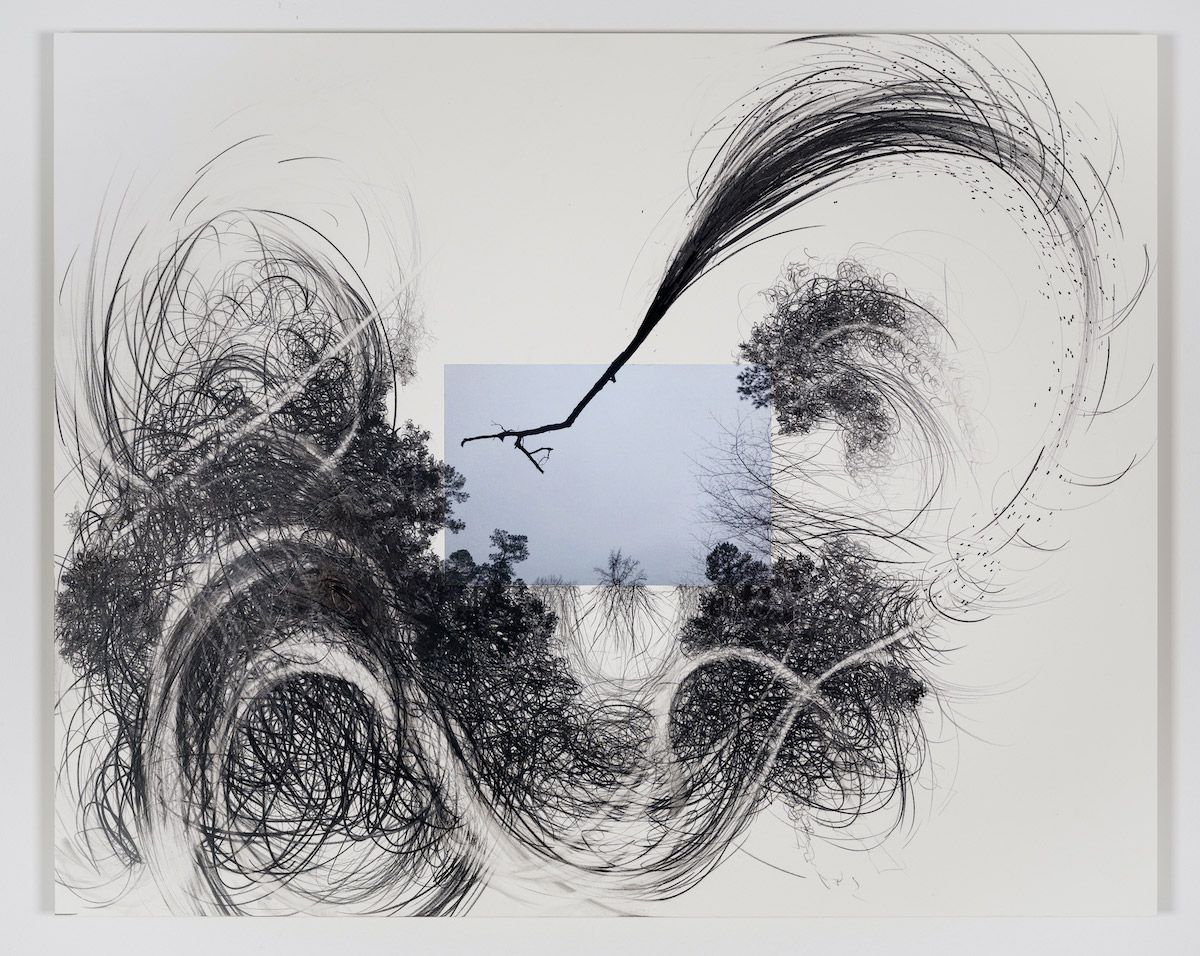

Kariann Fuqua, And Then There Were None, 2023, graphite, ink, and digital print on panel, 20 x 16 inches

Art, Climate Crisis, & Personal Journeys:

Allison Grant talks with Kariann Fuqua

In 2014, F-Stop Magazine ran a feature about my work, and this summer, I was honored when editor Christy Karpinski asked me to write a follow-up. She wanted to know how my life and work have evolved since the publication.

Interestingly, my journey in many ways parallels that of my friend and fellow artist, Kariann Fuqua. We both lived in Chicago after grad school and worked as institutional curators while pursuing our own art practices and teaching. Now, we’ve landed in full-time academic positions in the Deep South – me as Associate Professor of Photography and Director of Graduate Studies at The University of Alabama and Kariann as the Instructional Assistant Professor and Director of Museum Studies at The University of Mississippi. This fall, we’ll present a collaborative installation in New York City with the Intermission Museum of Art.

Our artistic practices converge on a critical issue: the climate crisis and ecological concerns. Given these overlaps, I wanted to have a conversation about how we’ve navigated art and life since graduate school. We spoke in July 2023.

—–

Allison Grant: Hi Kariann! Thanks so much for talking with me today. I know a bit about your career trajectory and I’m looking forward to learning more.

Let’s start by talking about what we were doing back in 2014. Having my work published in F-Stop was exciting, especially since it was just a few years after I finished my MFA in 2009. At that time, I was still trying to find my footing in the arts and figuring out my career path. I was juggling multiple roles, working part-time as a museum curator and educator, and also as an adjunct faculty member. But financially, I was struggling. What was that time like for you?

Allison Grant, Marsh, 2011, inkjet photograph, 30 x 40 inches, from the series Unsoiled

Kariann Fuqua: I finished my MFA in 2003 and began both adjunct teaching in Chicago while also working in a gallery, which I did for the next 5 years. Alongside my own studio practice, it was a lot to juggle, and I remember being in the same position, financially struggling.

AG: Yeah, it was definitely a time of uncertainty, but for me, there was also a vibrancy. I was hungry to figure out what contemporary art could be outside of graduate school and a formalized structure. What does it mean to make artwork, curate, and shape a curriculum? Those questions energized me. I didn’t have a lot of time to dedicate to my art practice, though, because so much of my energy was going toward writing, curating, and teaching. Was it similar for you?

KF: I was just starting my career so I was stumbling along and figuring it out. I was making a lot of work but because I was juggling teaching, gallery work, and painting, my personal life was sacrificed in the process. It felt like there was no room for rest and like you said, a sense of urgency, and looking back, I don’t really know why. An artistic career is such a long game, a marathon, not a sprint. I wish I could go back and tell my younger self to slow down just a little bit.

AG: I feel the same. There was an element, for me, of just thinking I’ve got to survive. If I slow down, I’ll lose it all.

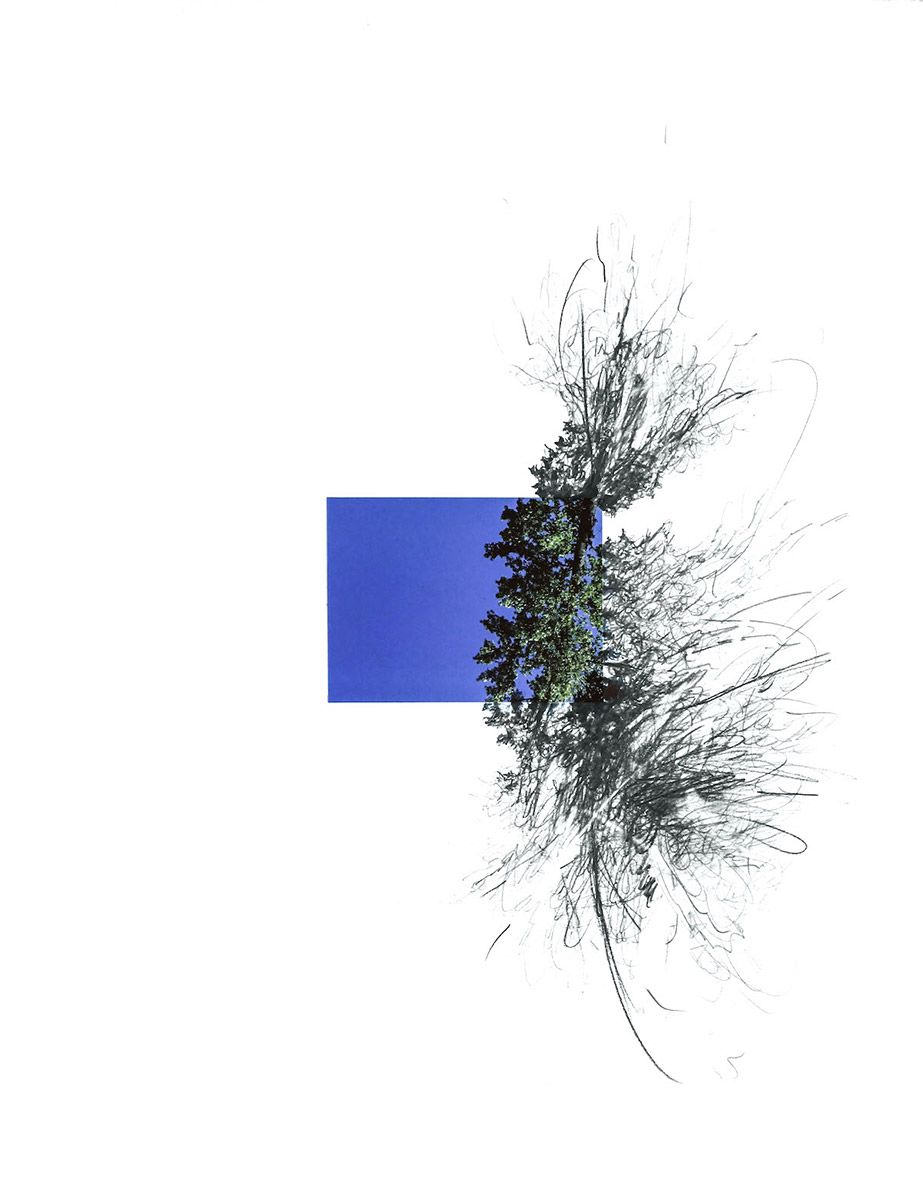

Kariann Fuqua, Facing the Storm, 2023, Graphite, ink, and digital print on panel

16 x 20 inches

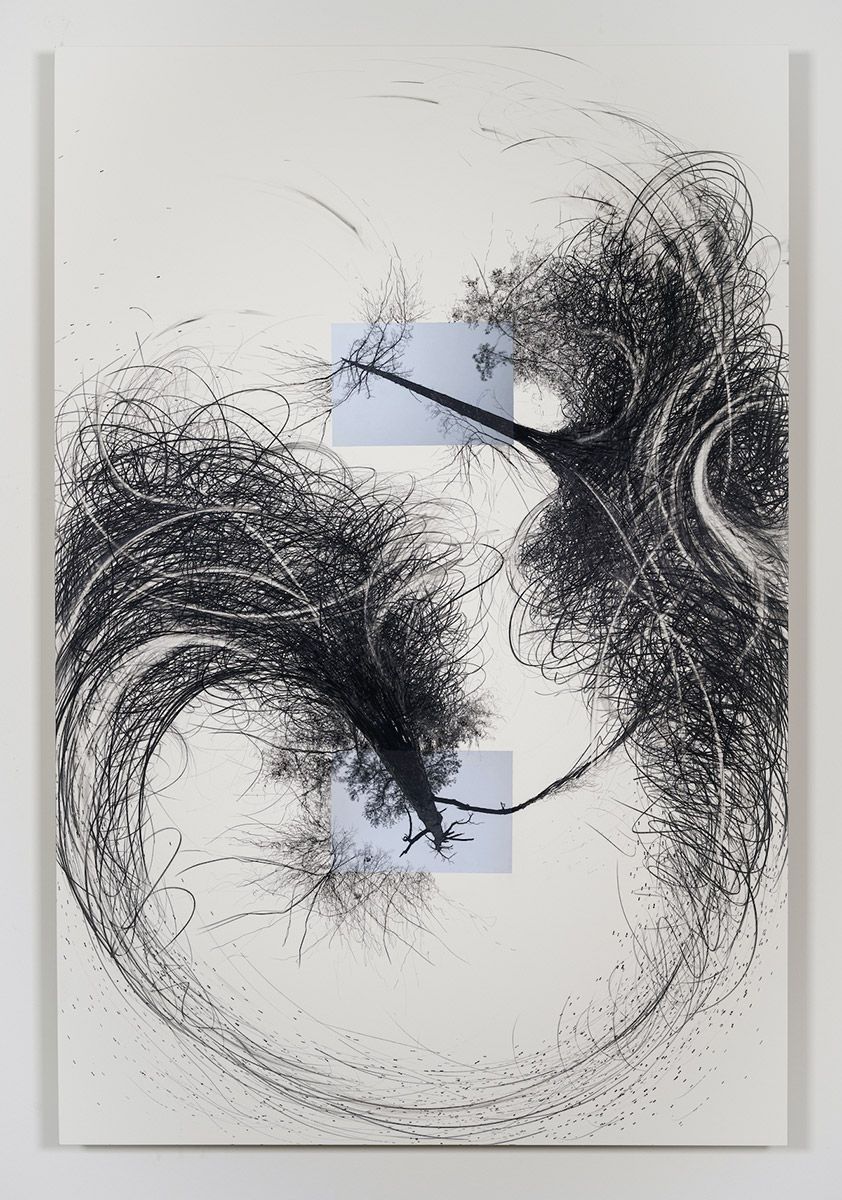

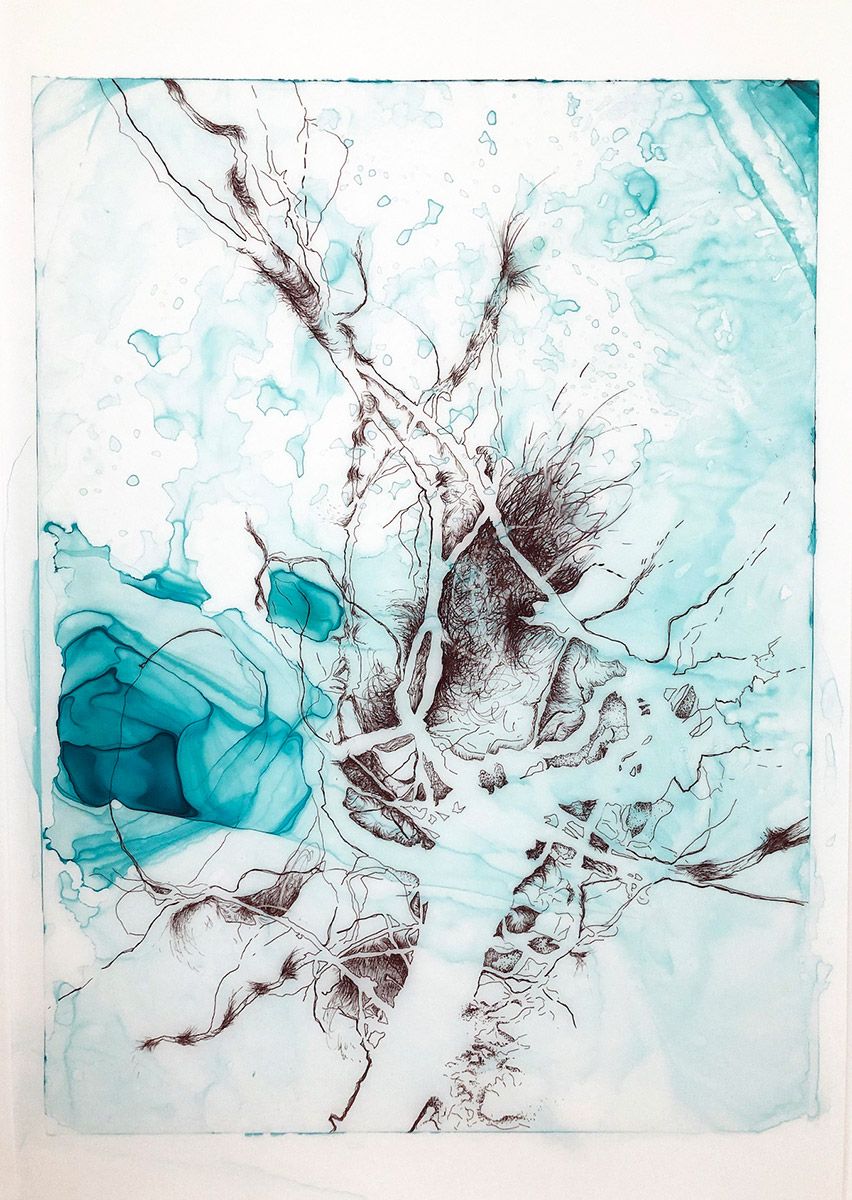

Kariann Fuqua, Feedback Loop, 2023, Graphite, ink, and digital print on panel

36 x 24 inches

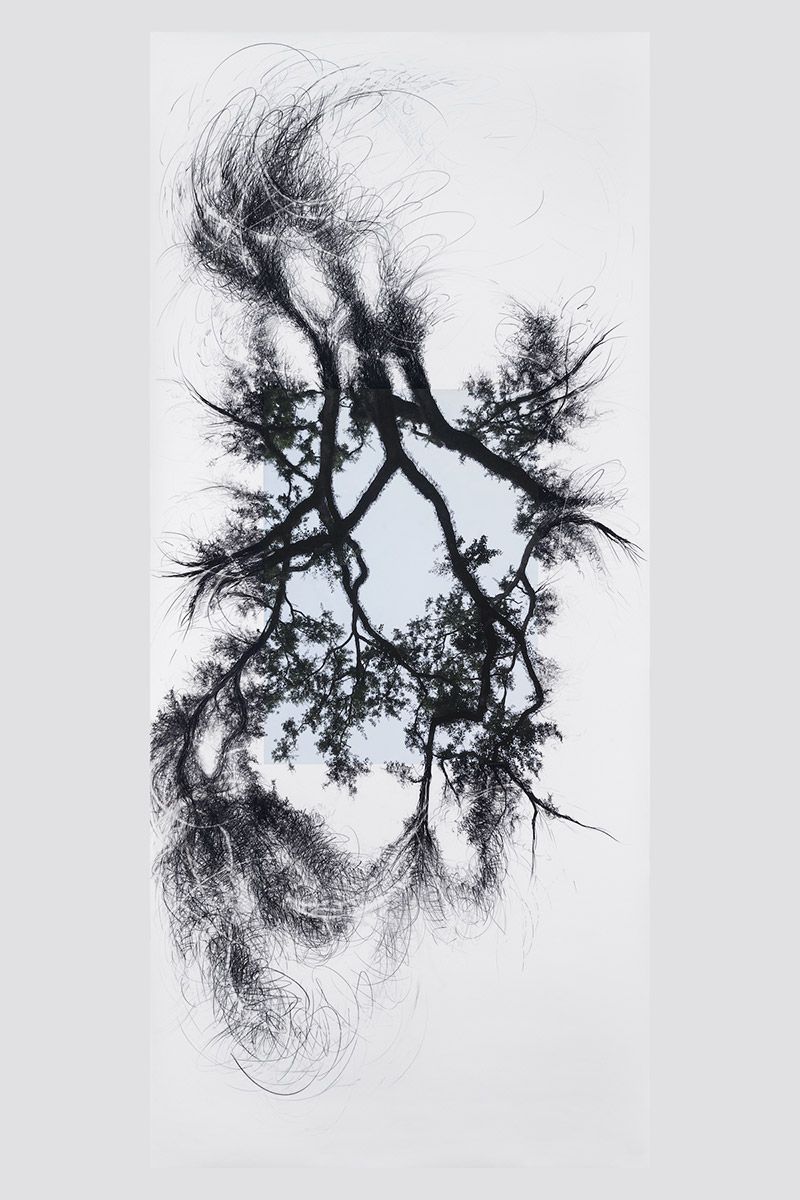

Kariann Fuqua, It Falls Around, 2023, graphite, ink, and digital print, 16 x 20 inches

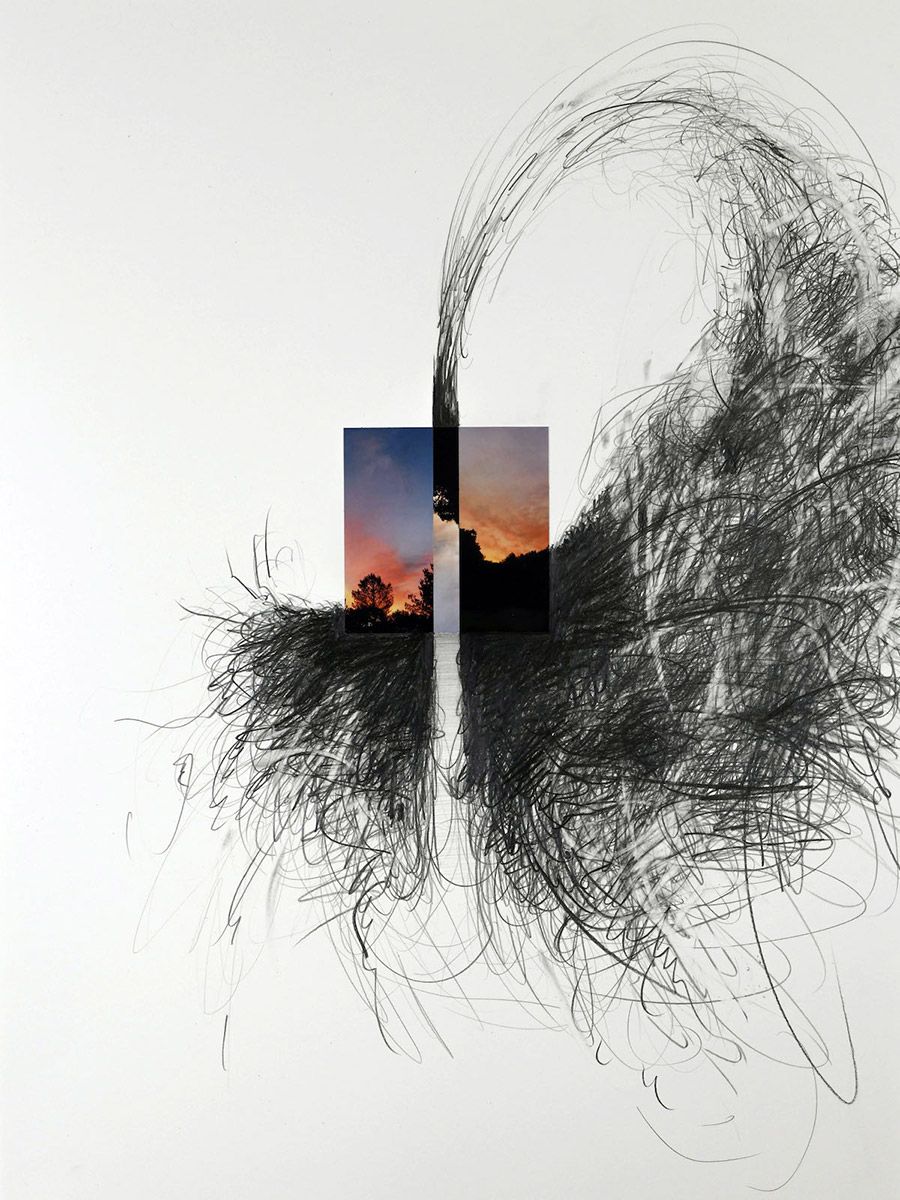

Kariann Fuqua, The Unraveling, 2023, Graphite, ink, and digital print on panel

96 x 42 inches

Kariann Fuqua, All the Things We Cannot See, 2023, Graphite, ink, and digital print on panel

96 x 42 inches

KF: Exactly! It was interesting, what you said about your personal practice being on the side when you were curating. And that definitely happened to me in 2012, when I started a full-time curatorial position 6 weeks after my daughter was born. I really wanted to believe that I could have an artistic practice and curate at the same time and the reality was that it just was not possible. My practice became nonexistent because there was no time, place, or headspace to even think about making new work. However, I did enjoy my time curating because it too is creative but the end product is different. Did you feel that way?

AG: Yeah, it’s definitely a creative act. I loved curating because I like riffing with other people and curation is inherently collaborative. Now that I work primarily as an artist, I really value opportunities to think alongside curators because so much of my creative work is done alone. I love having the space to make and think, but I get lonely sometimes.

KF: That’s definitely true. I think some of that is indicative of where we currently live. Coming from a large metropolitan area, it was a lot easier to engage with the creative energy of a city with so many other artists and museums surrounding you. Now that I live in a rural area, it’s been really challenging to find that community or see art on a regular basis when I have to drive great distances to do so.

Allison Grant, Petroleum Coke Storage Near the School, 2019, inkjet photograph, 36 x 48 inches

Allison Grant, As My Mother, So I, 2019, inkjet print, 40 x 30 inches

Shadow Mother, 2018, inkjet photograph, 30 x 22.5 inches

Allison Grant, Paper Mill Stacks, 2019, Inkjet photograph, 36 x 48 inches

Allison Grant, Thinking Child, 2019, Inkjet photograph, 22.5 x 30 inches

AG: Can you talk more about that? I’m interested in how place has shaped both of our practices. Chicago’s artists and institutions played an integral role in shaping my sensibilities as a visual artist. In 2016, I moved to the Deep South. Working here is a very different experience. How do you think about place in your work?

KF: Place plays an incredibly important role in my work and always has. I have moved around quite a bit in my life, and that migratory pattern influences how I see the world. I always think about my work in terms of mapping a particular place in order to acclimate to it. The visual language I used in Chicago was architecturally based, but I was breaking it down through abstraction to explore feelings of disorientation. The same is true of my work now but instead of giant skyscrapers and buildings, the imagery has been replaced by masses of forest and trees because that is what I am surrounded by. The landscape in the south is all-consuming. There is no sort of grounding to it.

Kariann Fuqua, Hamilton Teardown, 2007, Oil on canvas over panel, 24 x 24 inches

AG: That’s so true.

When you were working in urban spaces your paintings had a lot of angular and geometric forms, whereas I was working with imagery about the commodification of the idea of nature while living in the city. I was appropriating, modifying, and messing with “nature photography” that I’d encounter in media culture.

That’s the work that was originally published in F-Stop. I’ve never thought about it being about dislocation, but hearing you talk about your work, I think there are some parallels. My work changed when I moved out of the city. Here, I feel surrounded by these big, rich ecosystems. Alabama is sometimes called “America’s Amazon” because it has some of the country’s largest stretches of wilderness. There is also a lot of resource extraction and industry here. This place has changed the focus of my work toward ways that I might represent human integration with ecologies and environmental destruction. Instead of just thinking about how representations can define a false nature/culture binary, I’m trying to point more directly at my integration.

KF: I was thinking about this this morning on my morning walk. This is the first place that I have lived, where I’ve been able to grow food in a huge garden. Growing anything teaches you so much about the precariousness of biological life, the cyclical nature of time, and that there’s only so much we as humans can control. Nature really does its own thing with or without you on board. The act of gardening makes me understand the complexity of what we’re facing in terms of climate change. I understand in a very visceral way, that any actions that I take in this ecosystem have a reciprocal response, it pushes something in a particular direction and sometimes that’s good, and sometimes that’s really bad. I don’t know if I hadn’t had the space or time in which to learn this, that I would be necessarily making the work I’m making.

AG: I think that’s so profound. Are you trying to subsist with your garden exclusively?

KF: Ha! That’s a very lofty goal. I also understand how incredibly hard it is! I do grow enough throughout the summer that I can pull food we eat from my yard on a daily basis, which makes me extremely happy. It also fulfills this basic survival instinct, that I can subsist off something that I personally have put time and energy into, and it’s giving me energy back in the form of food. I’m also able to save enough for many months outside the growing season.

For some reason, it’s the one area in my life I’m never afraid to fail because I know at some point that’s part of the process.

AG: I’m probably less of a gardener than you are, but we grow some of our food. There is a way that my animalness becomes more apparent to me when I think about what it means to survive on food in my surroundings instead of a grocery store. The process of becoming a parent has made me feel more in touch with an animalistic dimension of my being, too. Nursing my babies – they were subsisting on my body’s milk production. I’d look down and think, wow, a year ago this kid wasn’t here and now they are a person—and this is how people have come into the world for as long as our species has been here. And of course, these kinds of feelings and instincts exist in people who don’t nurse or birth their babies—it’s really the miraculous, curious experience of care through parenthood that I’m talking about. It’s a place where I’ve felt intensely connected to something larger and deeply related to biology and ecology, and large, long spans of time. I wonder if it was that way for you.

KF: Yeah, definitely. One of the reasons I garden, and get my daughter involved in it as much as possible is because given the state of our world, it is a necessary skill that may have a huge impact on our survival. This information isn’t taught in depth in schools, but it should be. Also, gardening for me is a place of refuge, a place to rest. My garden provides a resource for so many other things beyond myself and my family. It’s not just a human-centered activity. But it’s really an effort to acknowledge the other lifeforms that make an ecosystem thrive.

AG: Yeah, I love everything you just said, especially the part about how this isn’t taught in school. The type of intelligence found in self-subsistence and care work is often dismissed. It’s really moving to think about how this informs your practice. And I think it influences my practice, too. I believe an essential part of how we navigate climate change going forward is this idea that we can’t only serve or value intelligence that props up capitalism. We need a social mindset that values sustainability as an intelligence critical to long-term existence—and one where we care for all people. And I think it starts very locally to yourself in your surroundings.

KF: I use the term radical care because that’s what it will take to get out of this mess. We have to start caring for the environment in ways that are not predicated on money, profits, or the bottom line. What does it mean to spend your time and your labor to produce/care for something? My little plot of land has so much abundance that I often give much of the food it produces to my neighbors and friends. With that, I’m also giving my time, energy, and knowledge to somebody else, with no expectations of anything in return.

AG: So much gift-giving is through obligation. And I think those little moments you’re talking about are incredibly special and meaningful. Are there other ways that living in the Deep South has influenced your perspective or your practice?

KF: I’ve come to the conclusion that people have a hard time understanding issues surrounding climate change because of its invisible nature and its evolution over long periods of time. It’s not until something so catastrophic happens that forces us to see how it impacts our lives. Living in the South, an epicenter for climate-related industry and natural disasters has definitely changed my practice. There is a visceral confrontation here that you can’t escape. Would you agree with that?

AG: I definitely agree, although I think fossil fuel industries and impacts exist in many places.

Kariann Fuqua, The Narrowing, 2022, Graphite, ink and digital print on paper, 28 x 22 inches

Kariann Fuqua, Boundary of the Unknown III, 2021, graphite, ink, and digital print on paper, 24 x 18 inches

KF: After living in Houston, and driving the corridor along the Gulf through Louisiana, and then up through Mississippi, I’m used to seeing massive refineries, chemical plant after chemical plant after chemical plant and the two are inextricably linked.

AG: That’s true, there are these vast swaths of the South that have been given over to chemical and fossil fuel industries. Once you see all of that – the scale and impact of it is haunting. And industry is often a lifeline here. Right? It’s the possibility of prosperity in a region that has been ignored and scapegoated.

Related to that, I’ve experienced a lot of bias against the South from friends who don’t live here. There is a political tension where many people from the north vocalize thoughts about how no one would want to live here given a choice. Sometimes, within that, I think there is a subtext that what happens to people here doesn’t matter or is self-inflicted. There are so many wonderful, brilliant people here who are doing amazing work, and who are fighting so hard to make the South a good place. Those types of comments are a form of erasure of their contributions to a common cause.

I also think about what it means to be a teacher and artist here and to be among a smaller community, but to also know that there are possibilities that are undervalued and different from the “center” of the art world.

KF: The South is deeply complex and layered in so many ways I’m still learning about. But I’ve also been asked the same question about why I moved here.

AG: Well, one of the reasons that I moved to Alabama was because I was offered a job here as an academic.

KF: Me too. When opportunity comes you take the place with the job.

AG: I wanted to talk to you about that, because we both moved away from curation. It’s not our primary role any longer. We’re both professors and artists who also curate sometimes. I wonder about what that decision was like for you.

KF: My entire career has been nonlinear and has sometimes been dictated by opportunity and also by being married to another academic. We have made choices to move around because of both of our careers and that doesn’t neatly follow any particular path.

I did love curatorial work, and I still love thinking about the kind of storytelling and synergy that happens when curating an exhibition. But as an artist, I am compelled to make and needed to get back to that. I also love teaching, being in the classroom with younger artists helping them build a creative life. What about you?

Allison Grant, Black Water, Texas Creek Contaminated by Mine Leak, 2021, Inkjet photograph, 36 x 48 inches

Allison Grant, Mother Cover, 2019, Inkjet photograph, 36 x 48 inches

AG: It’s similar. Earlier, when you were talking about wanting to be an artist and a curator simultaneously while also teaching—I completely understood that bind. Maintaining those three things was probably impossible before I had children but once my first child was born, I remember thinking, “This can’t really go on.” I mourned my life as an artist because I thought it might be over, then decided I would apply for a round of teaching jobs so I could get back to making. I got an offer from The University of Alabama.

Throughout my career trajectory, and my life as an artist, I think I’ve been really delusional about what’s possible. I never wanted to have kids, but my partner did. I’m glad we had kids because I love being a parent, but I never had a female professor on the research track who had kids—who was a mother. And when I came to The University of Alabama, I was the only mother on the tenure track. I posted something about this on Instagram and a high school friend of mine—we were both the ones in the darkroom after school every day—she generously commented that she abandoned a photography degree and became a designer because she couldn’t see a path to having a family and an art career. If I’d had that foresight, I’m not sure what I would have done. It just seems like it’s a very difficult thing to make it all balance, and yet some days I love it for its intensity.

But part of the reason that I came to Alabama was because it was the job on the table. I didn’t expect this place to influence my work nearly as much as it did because I didn’t recognize how much Chicago influenced my work until I left. I knew, coming to Tuscaloosa, that I wanted to make work about what it feels like to be among the first generation of parents raising their kids in the early stages of climate change. I didn’t know how I was going to craft that until I got here, and the land has become a surprisingly important part of that.

KF: It’s interesting that you said that you didn’t think you wanted to have children. I felt very similarly. There seems to be this prevailing myth in the art world that you can’t be a mother and a serious artist at the same time. When I was in grad school, there was only one professor with a child and there were no discussions about how one navigates family life with an artistic practice. Now that I am a mother, there is a complete shift in the way that I make work than before I had a child, but the work still happens. I wonder at what point that myth is dismantled. Both of us have flourishing studio practices. And we’re raising children. And we’re also teaching students. And we’re juggling all of those things simultaneously. I’m not saying it’s easy but it can be done if we get the support we need.

Kariann Fuqua, Rupture, 2022, Ink and Watercolor on Mylar 36 x 24 inches

Kariann Fuqua, Trajectory, 2021, Graphite, ink, and digital print on paper, 18 x 14 inches

AG: I think that’s true. And I owe so much to my partner and my family because they work so hard to help provide space for me to pursue my work. But you know, I was reading this article recently in the Harvard Business Review by two gender inequity scholars, Robin J. Ely and Irene Padavic. Their research into why there are so few women in executive leadership has shown that women tend to take accommodations for family and men tend to not take accommodations. Therefore, men get promoted to the highest levels because they’re not taking maternity leave, or they’re not shouldering as many aspects of care work, but actually, both partners suffer. Most parents want to be present in their kids’ lives and everyone is sacrificing so the company doesn’t have to mind boundaries and offer people time to have a home life. And of course, we know there are people who are impacted by these dynamics while parenting in non-binary relationships or as single parents. And actually, the problem is not the workers. It’s the structure. We need structural change that makes it possible for people to leave work at five. We need quality childcare that’s affordable and available when people need it, not exclusively during traditional work hours. We need living wages for adjuncts. If a graduate student has a baby that shouldn’t mean they are shut out of higher education because they can’t make the impossible wages and hours work. I feel fortunate and lucky, but it shouldn’t be years of sacrifice and extremely good luck that lands only a few of us on stable ground. I know it could have happened in a totally different way for me, and I wouldn’t be an artist. And I think a lot of parents would be making really meaningful art if they hadn’t had to leave. We need to normalize a living wage and the end of the workday.

KF: There are so many systems that intersect here. We both have spent a good deal of time in higher Ed with its own hierarchal political and economic systems of expectations/oppression of people, laborers, and women. I, too, am at this point where I’ve gotten tired of being silent. And we’re in positions where we can work towards meaningful change, even in small ways, like not having a faculty meeting at 3’clock in the afternoon when we have to pick up our children.

AG: Yes, department chairs, you can make that happen. My chair has instituted family-friendly policies like no meetings outside of regular business hours and we all still get our work done.

Thinking about future trajectories, what are you working on now?

Allison Grant, Me Gripping Baby, 2019, Inkjet print, 30 x 22.5 inches

Allison Grant, Acid Mine Drainage, 2020, Inkjet print, 30 x 22.5 inches

Allison Grant, Cicada Shell, Caught Red Handed, 2019, inkjet print, 30 x 22.5 inches

KF: I recently completed 3 of the largest drawings I have ever made (8ft tall) for the Mississippi Invitational at the Mississippi Museum of Art, and those drawings were a big technical, conceptual, and physical leap in my practice. I have several solo shows coming in the next few years where I will continue mining my interest in grief and loss, hope, and resilience of biological systems at play in our unknown future. I am considering the possibility of drawings becoming ephemeral and incorporating the plants I grow or other three-dimensional found material into my work. Essentially, I’m experimenting with ways to make art that has less of an environmental impact, increasingly concerned about material use with what I’m putting into the world that can’t be taken back out. I don’t know where this will lead but I’m excited by the possibilities. What about you?

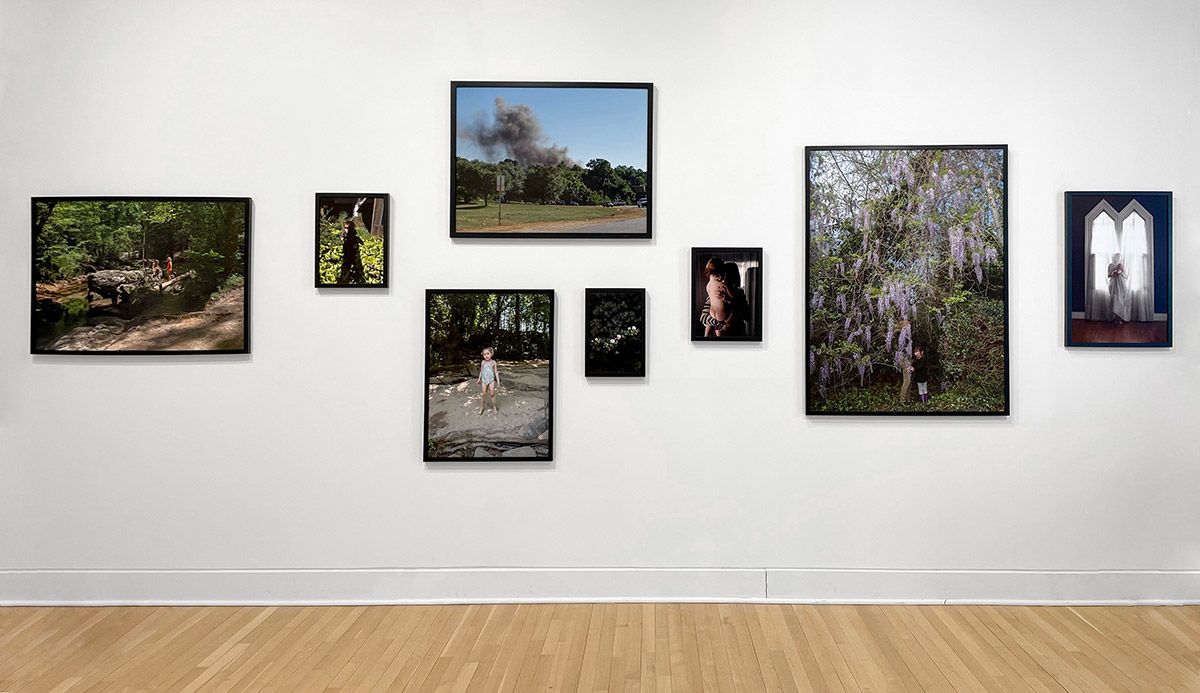

Installation view of works by Kariann Fuqua from the group exhibition Gulfs Among Us, curated by Katie Pfohl at the Mississippi Museum of Art in 2023

AG: I’ve been working on this long-term autobiographical photographic project, Within the Bittersweet, for six years and I’ll probably continue it for many years to come. I’m also starting a new body of work that looks at energy production in Alabama through fossil fuel extraction and solar energy, and the communities that form around those industries.

Installation view of works by Allison Grant from the group exhibition Perpetual Ebb, curated by Eli Craven at Purdue University’s Rueff Gallery in 2022

KF: Oh, I can’t wait to see it. it’s so exciting to have new ideas and room to explore them in ways that feel very unencumbered.

AG: Yes, and it’s interesting that we’re both turning outward a little bit. There are questions that have come up within both of our practices. For me, I’ve been thinking about how coal is toxic but also provides livelihoods to good people in my community. How do I deal with that complexity? You are thinking about how the material character of your work has an impact beyond its appearance on the wall. Having been a practicing artist for many years, I’ve found I have to trust that the work is going to show me the next questions.

KF: Exactly. It doubles what we’ve been talking about, this life of the unknown, and that there is no certain future. While that’s a terrifying idea, it’s also very liberating because we can investigate complex non-binary ideas in whatever way seems fit. It’s wildly freeing not to put yourself in a box, letting the work unfold over time and guide shifts in direction.

AG: yeah, I love the way you put that, and look forward to watching what happens next for both of us.

Events by Location

Post Categories

Tags

- Abstract

- Alternative process

- Architecture

- Artist Talk

- Biennial

- Black and White

- Book Fair

- Car culture

- charity

- Childhood

- Children

- Cities

- Collaboration

- Cyanotype

- Documentary

- environment

- Event

- Exhibition

- Family

- Fashion

- Festival

- Film Review

- Food

- Friendship

- FStop20th

- Gun Culture

- Italy

- journal

- Landscapes

- Lecture

- love

- Masculinity

- Mental Health

- Museums

- Music

- Nature

- Night

- photomontage

- Podcast

- Portraits

- Prairies

- River

- Still Life

- Street Photography

- Tourism

- UFO

- Wales

- Water

- Zine

Leave a Reply