blog

Book Review: Eight Seconds: Black Rodeo Culture by Ivan McClellan

Marland Burke, Brandon Alexander, James Pickens Jr. Los Angeles, California. © Ivan McClellan

Ivan McClellan, a New York Times photojournalist and Kansas City native, has made significant contributions to the recognition and understanding of Black cowboy culture. His new book, Eight Seconds: Black Rodeo Culture, published by Damiani Books, shares his dedication to documenting the unique subculture. This long-term project began during his coverage of the Roy LeBlanc Invitational Rodeo, the oldest annual Black rodeo in the United States. The journey over the next decade took McClellan across the country and introduced him to lifelong friends. From rodeos to ranches, he documents the lives of these extraordinary people. This work sheds light on Black cowboy culture, elevating their stories in popular media. Ivan’s work centered on Black rodeo culture not only disrupts common perceptions, but also celebrates this part of his identity he fully embraces. His ‘Eight Seconds Project’ aims to broaden the cowboy icon to feature people of color, ensuring their integral role in Western heritage is acknowledged and celebrated.

‘Eight Seconds’ celebrates Black cowboy culture by concentrating on narrating the culture as it is now. McClellan says he is aware and well versed in the history behind Black cowboys, how the job evolved after the civil war, and he makes sure to stress that that history is very important. His work focuses on the story of current Black cowboy culture, versus blatantly framing it in contrast to the past. Black cowboys, and specifically Black rodeo culture, has endured and gained respect on its own, regardless of how it is or is not portrayed in the media at large. ‘Eight Seconds’ captures and embraces the lifeblood that flows through a culture that’s been described as a piece of living art. Because of Ivan’s sincere desire to fully integrate himself into the culture, he is able to display this respect in his work with such earnestness. And for that reason, his work has an undeniable authenticity that captures this rich culture.

I was fortunate to meet and talk with Ivan at the end of February this year when he was in Indianapolis to unveil three of his photographs which are now in the permanent collection at the Eiteljorg Museum. Ivan was generous with his time and took time to talk with me and field many questions from the public and invited guests about his work and the long-term ‘Eight Seconds’ project. (The book’s title refers to the sport of bull riding where athletes must stay on a bull for eight seconds while it tries to throw them off; the more frantic the ride, the higher the rider’s score.)

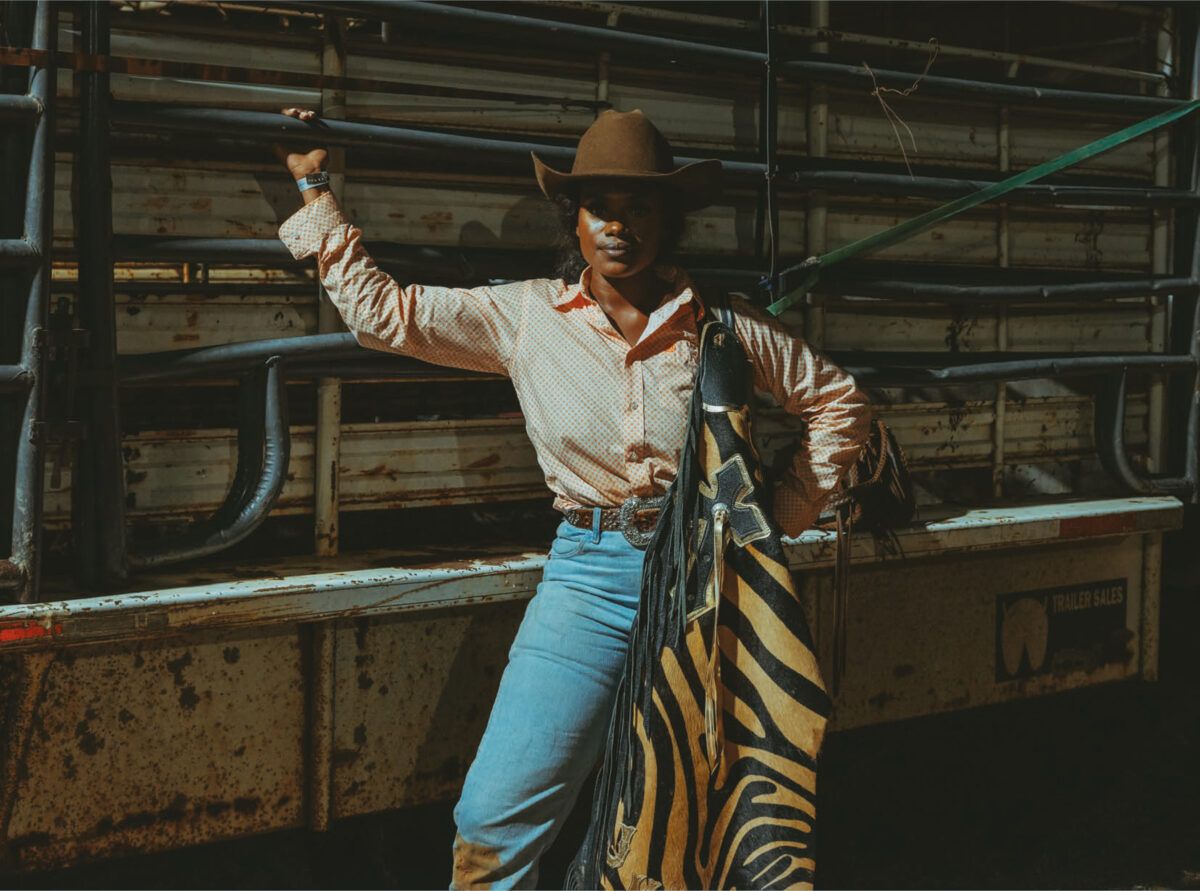

Perhaps not surprisingly, much of Ivan’s discussion centered on the topic of access and how the project has been received by mainstream media and audiences. A point Ivan makes sure to mention is that the people and scenes of Black rodeo culture in his photos do not fit the Hollywood stereotypes. The proverbial hero’s white hat, colorful silk scarf, and crisp shirt on the whole are a misrepresentation. The sport of rodeo and riding is dirty, difficult and dangerous, plain and simple. Ivan’s work brings a majesty, respect, and even reverence to his rodeo subjects. Ivan notes that white photographers can create good photos at a Black rodeo, but there is no comparison to his inclusive approach. “That is what Black folks, people of color, bring to photographing other people of color,” Ivan explains.

Kortnee Solomon, Hempstead, Texas, 2020 © Ivan McClellan (One of three McClellan photographs in the permanent collection of the Eiteljorg Museum of American Indians and Western Art)

Scrawney Brooks, Liberty, Texas, 2022 © Ivan McClellan (One of three McClellan photographs in the permanent collection of the Eiteljorg Museum of American Indians and Western Art)

Southside, Bristow, Oklahoma, 2021 © Ivan McClellan (One of three McClellan photographs in the permanent collection of the Eiteljorg Museum of American Indians and Western Art)

Rodeo Queen, Okmulgee, Oklahoma. © Ivan McClellan

Ivan often tells personal stories about the people in the photos, his family, and how growing up in working-class family in Kansas City was an important foundation for his involvement with Black rodeo culture. The neighborhood from his youth was a distinct mixture of urban and country. We see this reflected in his images of some rodeo riders who are dressed in basketball shoes along side riders with square toe boots. We see a group of barrel racing riders laser-focused on their impending start. One if Ivan’s images features a glinting gold watch and lug-nut-sized rings adorning the chapped hand of a horseman, and we see cowboys with dreadlocks wearing tank tops and bib overalls in contrast to the coifed hairdo and dazzling blouse of a young rodeo queen proudly sitting atop her horse, smiling knowingly into the camera.

Patrick Liddell, Las Vegas, Nevada. © Ivan McClellan

Bull Riders, Rosenberg, Texas. © Ivan McClellan

Jadayia Kursh, Okmulgee, Oklahoma. © Ivan McClellan

“There were lowriders and gang members on our block and the street would get lit up at night by police helicopters,” Ivan remembers about his childhood in Kansas City. But every summer, he and his sister would run around the two-hectare field that lay behind their house, eating blackberries and catching lightning bugs.

“Some of our friends at school had cows and chickens and we’d see people trotting down the street on horses,” Ivan recalls. “But I never thought of our upbringing as country, or the Black folks around us as cowboys. The only Black cowboys I ever saw was like Cowboy Curtis on Pee-wee’s Playhouse or Blazing Saddles,” Ivan shares. “But I came to realize you could be a Black cowboy and live in the middle of Philadelphia, in big cities. They rodeo, they drive trucks, they do a lot of the things that you expect the cowboy to do, and a lot of those Hollywood stereotypes got broken. And you see guys riding horses in Jordans, and you see guys riding horses in basketball shorts with no shirt on and gold chains and earrings. And they look like a figure that you would expect to see in a rap video or you expect to see out of hip hop culture, but they’re absolutely cowboys. They raise horses, they live on farms. And so it really kind of shattered a lot of my own conceptions and really forced me to change the way I thought, and my thought process.”

Much of that change started to happen in 2015, when documentary filmmaker Charles Perry invited McClellan to the Bill Pickett Invitational Rodeo, the only touring African-American rodeo in the world. Founded in 1984, the Bill Pickett Invitational Rodeo brings its iconic celebration of Black cowboy culture to every corner of the country. Ivan attended the rodeo wearing a Kansas City Royals baseball cap in Okmulgee, Oklahoma in the middle of the August heat, soaked through in flop sweat, and he became immediately hooked on a culture that reminded him of home.

“As soon as I step into the arena, I relax,” he says. “It’s a feeling of familiarity and being surrounded by family. I met people at the Okmulgee rodeo that grew up in my neighborhood. I felt like I had discovered an entirely new interpretation of my home. Every rodeo, Black or White, is steeped in patriotism and America. Black rodeos are no different… except instead of the American flag, a lone rider lopes around the arena carrying a red black and green Pan-African flag. After a rendition of ‘The Star-Spangled Banner’ by Whitney Houston or Beyonce is played over the loudspeaker, and a live performer sings ‘Lift Every Voice and Sing’, the Black national anthem, with so much fervor that you feel it in your soul.”

McClellan has travelled the nation documenting the Black cowboys and the rodeo circuit they have developed to celebrate their heritage. His work speaks about the importance of community, and the joy and respect for the rodeo athletes he has photographed and come to know over the years. McClellan now proudly hosts his own rodeo (the Eight Seconds Juneteenth Rodeo) in Portland, Oregon where he lives with his family.

Dontez & Floss, Okmulgee, Oklahoma. © Ivan McClellan

“My grandma was super confused when the whole thing started. Because…” Ivan slowly explains, “we didn’t know there were horses on the other side of the field where we played as kids… my grandmother didn’t want us to know. Horses and all that country stuff is where they came from. They grew up on a hog farm, and you know, they didn’t want that for us. They wanted us to hang out in the city, and go to museums and go to plays… and not get involved in horses. And I just migrated to it anyway,” McClellan laughs. “To them, country equals poor. But when my family saw how Black cowboy culture elevated people, they came on board.”

“My mom cooked for all the athletes at that first rodeo, brisket, mac & cheese, green beans, red velvet cake… Mmm, right?” Ivan prompts the crowd in Indianapolis. “She cooked for two days for 40 athletes. It was the highlight of the rodeo for the riders because nobody else does that for them.”

That sense of community and family, ultimately a sense of belonging, comes across in Ivan’s images in ‘Eight Seconds’. His ease with folks he meets, and the trust forged before he even thinks about shooting photos shows in their eyes. Ivan also tells the heartbreaking story of his friend Ouncie Mitchell, a rider who overcame personal struggles and became a champion rodeo rider, only to be shot and killed soon after. His personal connection comes through as a friend, a colleague, and a fellow Black cowboy. Yet Ivan confessed that early on in the project he very much felt like an outsider. A poser not worthy of wearing a cowboy hat. “I used to ask folks how they got interested in being a rodeo rider, working with horses and such,” Ivan remembers. “They would just stare at me with this blank look. The idea of Black cowboy culture, and how folks fit into it,” Ivan explains, “it’s just a matter of fact. That’s their life. It’s not something you grow into, not something someone gets interested in,” and he adds with a warm laugh, “It’s like asking you how you got interested in eating bread.”

The quiet strength of ‘Eight Seconds’ is in sharp contrast to the dizzying chaos of a bull and rider thrashing their way around the rodeo ring. The softer, more intimate photos in the book display both the pride and determination of cowboy culture. We see this in photos capturing a quiet moment between a father and his son or daughter, a whole family standing together in front of their horse trailer, or Ivan’s image of a prayer circle before the start of a rodeo. These quiet photos may juxtapose the wild, stereotypical image of a rodeo, but Ivan’s masterful eye shows us that they aren’t two different cultures, they are one and the same. He brings it all together to create, highlight and celebrate these stories, allowing for a fuller and richer experience and representation of Black cowboy culture.

::

Eight Seconds: Black Rodeo Culture by Ivan McClellan

Hardback 128pp 118 color 285 x 230 mm

Edited by Miss Rosen

Foreword by Charles Sampson

Published by Damiani Books

::

Ivan McClellan (born 1983) is a New York Times photojournalist based in Portland, Oregon. McClellan is the Founder and CEO of Eight Seconds and the Eight Seconds Rodeo and the creator of the Eight Seconds Project, a storytelling project with the goal of extending the cowboy icon to include people of color. Since 2015, Ivan’s work has helped tell the story of Black cowboys to a national audience, even working on campaigns with iconic Western brands such as Stetson, Wrangler, Boot Barn, and Tecovas.

Location: Online Type: Book Review

Events by Location

Post Categories

Tags

- Abstract

- Alternative process

- Architecture

- Archives

- Artist residency

- Artist Talk

- Biennial

- Black and White

- Book Fair

- Car culture

- Charity

- Childhood

- Children

- Cities

- Collaboration

- Community

- Cyanotype

- Documentary

- Environment

- Event

- Exhibition

- Faith

- Family

- Fashion

- Festival

- Film Review

- Food

- Friendship

- FStop20th

- Gender

- Gun Culture

- Habitat

- home

- journal

- Landscapes

- Lecture

- Love

- Masculinity

- Mental Health

- Migration

- Museums

- Music

- Nature

- Night

- nuclear

- Photomontage

- Plants

- Podcast

- Portraits

- Prairies

- Religion

- River

- Still Life

- Street Photography

- Tourism

- UFO

- Water

- Zine

Leave a Reply