blog

Interview with featured photographer Sasha Hitchcock

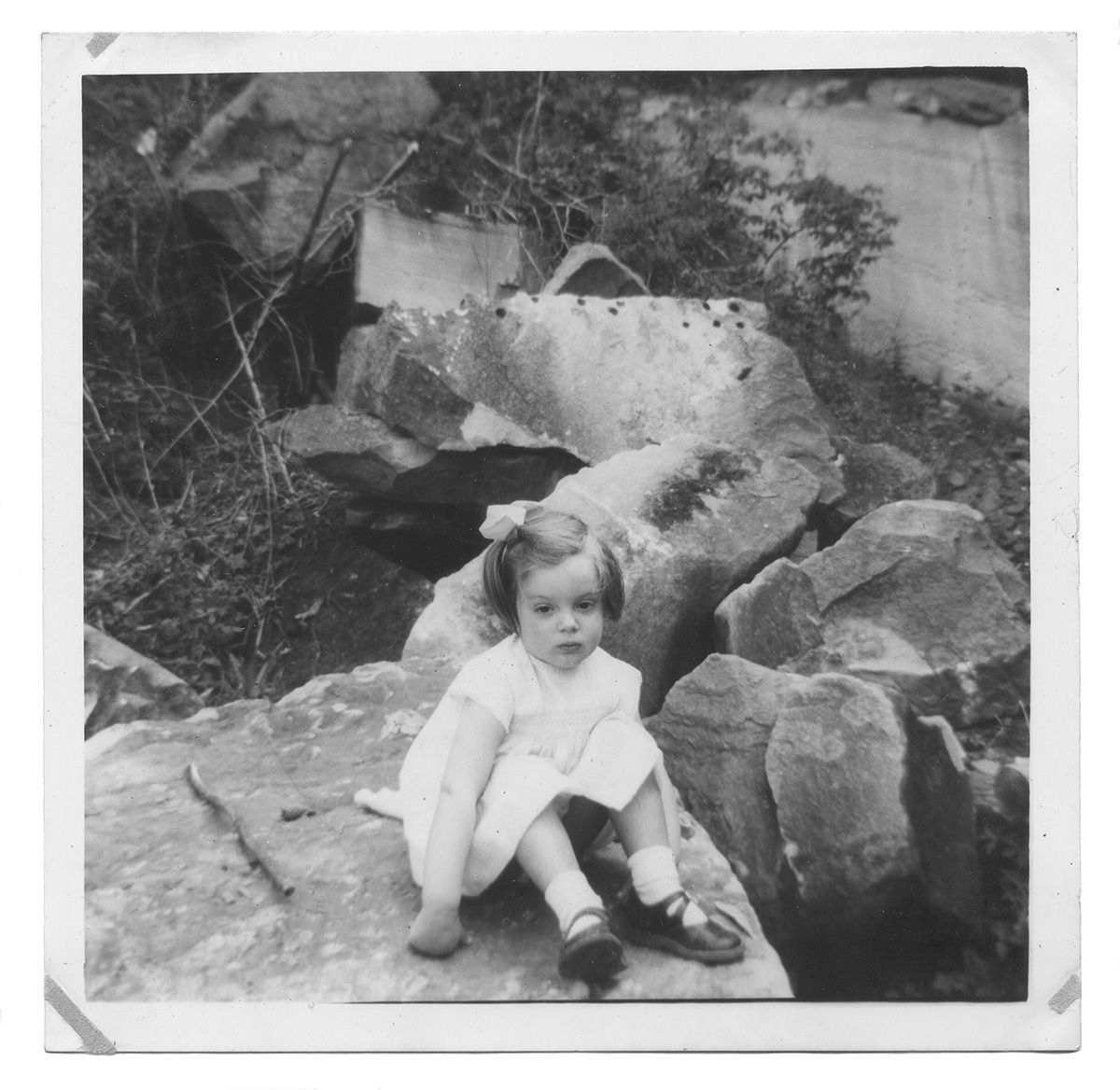

from ‘Skeleton Woman’ © Sasha Hitchcock

For the Open Theme of Issue 131, we have the privilege of featuring the work of Sasha Hitchcock, a UK-based photographer whose work delves deep into the human psyche. Her featured portfolio, “Skeleton Woman,” is a profound expedition into the self. Described as a “treasure map-like journey,” the project bravely navigates the often unseen realm of the psychological shadow-self, aiming to reclaim lost aspects of the artist’s past. Her project was born from an unfulfilled desire to connect with her own history, and “Skeleton Woman” masterfully juxtaposes Hitchcock’s contemporary photographs with images from her grandfather’s archive, creating a unified yet deeply personal narrative. It’s a testament to creativity as a resource for healing, understanding, and confronting fear, offering a unique glimpse into the lonely yet ultimately empowering process of self-reflection.

::

Cary Benbow (CB): What is your earliest memory of taking photos?

Sasha Hitchcock (SH): My parents would buy me little disposable cameras whenever we went on holiday. For some reason, when I was in another country, I felt the most at peace. A lot of my physical symptoms would subside and each time at the end of the holiday I would have a great desire for the adventure to continue. I think from a very early age there was a draw towards taking a journey, it just so happens that so far that pilgrimage has been internal rather than external.

CB: “Skeleton Woman” is described as a treasure map-like journey of seeking, a pilgrimage into the “psychological shadow-self. Could you elaborate on the initial spark for this personal exploration, and how you recognized that photography would be the most effective medium to navigate these internal landscapes? What makes photography your medium of choice?

SH: As with all my projects, I often have little to zero idea on what the body of work is actually about whilst I am creating it. I tend to have areas of interest that inform the work and then I surrender to allowing the project to navigate itself. I think I increasingly believe that we are just the physical vehicle to allow life/God/the Universe, whatever one might subscribe or not, to work through us.

My experience of life at the time was as if I was living in a haze. I felt as if there was a video tape playing over day-to-day existence and yet I could not see the content of it. I moved in and out of an incredible variety of atmospheres bringing with them a unique poignancy that would influence how I was showing up in the world. I also had little access to visual memories from most of my life that alongside challenging physical and emotional symptoms led me on the journey of seeking to reclaim what was lost. On reflection, I think I was attempting to use the camera to capture something that my conscious self could not see.

I have recently come to the awareness that of all the senses, the visual was always the sense of choice that I would prefer to use the least. I would navigate the world looking at the ground or the sky, unconsciously choosing to stay disconnected from my visual environment. Obviously, that is incredibly fascinating that of all the arts I was drawn to the medium where ‘looking’ is the main feature. Perhaps unconsciously, it was a part of me that understood that Photography was a path back ‘home’. I believe that deep down we all know the path that we must walk to find ourselves.

from ‘Skeleton Woman’ © Sasha Hitchcock

from ‘Skeleton Woman’ © Sasha Hitchcock

CB: You mention the “incredibly lonely process of self-reflection” for your project. How did the act of creating these images, especially in their eventual form as a monograph, transform or perhaps even mitigate that loneliness? Was there a point where your creative process itself became a form of catharsis or ‘companionship’?

SH: I would say that the experience of the project compounded my loneliness. But that was an illusion and a common one that is experienced as a result of facing the aspects of ourselves we usually choose to ignore. Through the work, I was coming into direct relationship with the loneliness and feelings of abandonment that I had spent a lifetime ignoring. So, the work actually documents a fairly vicious spiral into the depths of the underworld and the illusion of deterioration to find what was lost all those years ago. An uncomfortable truth of delving into the shadow-self is that we often must come into relationship with our own insanity to find the possibility of wholeness. My relationship with Photography has always been a turbulent one because it is evidence of truth that I often chose to ignore. Photography can be the mirror to the parts of ourselves that we do not want to acknowledge exist inside of us. It is through the craft that all the parts of me that have not historically been given a voice get to speak their truth for first time. And so yes, I guess there was a development of companionship, but it was with myself through the craft, rather than with the medium itself.

CB: The psychological aspect of this project is an interesting aspect of this project. How did this therapeutic process directly influence the visual vocabulary you developed for “Skeleton Woman”? Were there specific dreams or insights from these sessions that found their way, either literally or metaphorically, into your photographs?

SH: All the work was produced very organically and so there were never any pre-planned or conscious decisions made about what to photograph. I think the work I undertook with the psychotherapist helped me to intellectually understand the process, whilst providing a continuous focus on and interest within the polarity of unconscious/conscious and dreaming/awake. That opposites are the same, differing only in degree; everything is and isn’t, at the same time; all truths are but half-truths, every truth is also half-false. Within Photography, are light and darkness not the same thing? The difference consisting of varying degrees between the two poles of phenomena. Where does darkness leave off and light begin? And so, what is conscious and unconscious; dreaming and awake, if not one and the same thing?

from ‘Skeleton Woman’ © Sasha Hitchcock

from ‘Skeleton Woman’ © Sasha Hitchcock

CB: The juxtaposition of your images with your grandfather’s archive is a powerful narrative choice. How did you approach the selection and integration of his photographs? Were there moments of unexpected resonance or dissonance between your work and his that truly shaped the final unified narrative?

SH: I ended up sitting on the body of work for several years due to fears that by working with a publisher that the content would somehow be corrupted away from its true essence. I resigned myself to the idea that I would have to self-publish but I felt unequipped to do so. I was connected with Jaime Molina, who runs Orange Press, and he was interested in the project. At our first meeting, I felt that he instantly connected with and understood what Skeleton Woman was about, and that we also shared a very similar outlook on life. I recognised that not only was he incredibly talented at editing, but that he was able to find answers to questions that I had and vice versa. It really has been a profound and fulfilling experience of collaboration. I think we have both been intuitively led by the photographs and often find it interesting when viewers of the work pull out themes that we had not consciously recognised.

My grandfather’s photographs are obviously incredibly beautiful, and I think that he might be a better photographer than me. But I do feel that there is strangely some kind of unified vision or way of seeing the world that manifests across both our images.

from ‘Skeleton Woman’ © Sasha Hitchcock

from ‘Skeleton Woman’ © Sasha Hitchcock

CB: You describe the work as born from an unfulfilled desire to seek answers about the past, resulting in a one-sided conversation with the self. In what ways did confronting this unfulfilled desire through your creative process, and ultimately publishing your upcoming book, offer a sense of resolution, even if the answers were difficult to pin down?

SH: I think one of the main sources of development that has come because of the work is my understanding of memory and love. At the time, much of my desire to seek was born out of not having access to the visual part of memory, but what I came to understand was that memory was not just a visual experience. That it spans many different senses and is often present with us in this very moment.

I think the desire to seek answers really is the longing to be seen and loved for who you are, to know that you are enough just as you are. That in fact, you were always whole. So, whilst I look at the body of work and find it disconcerting because it reflects an uncomfortable period of my life, the resolution is experienced in the understanding that it was a necessary and ultimately beautiful process to lead me to where I find myself now.

CB: Creativity can be used as a resource to tap into hope and understanding, inner strength and love; can you pinpoint a specific image or series of images within “Skeleton Woman” where you felt this transformative power of creativity most acutely, where the act of making truly led to a breakthrough in self-understanding?

SH: I think I view the act of making as an experience of being ‘tapped on the shoulder’, an attempt to bring awareness to aspects of the unconscious. In meditation or mindfulness, you are often taught to show up to this very moment without attachment. I am unsure how many people recognise how very difficult that actually is, that it may require a lifetime of work to achieve. My photographs were providing me with all the answers that I was seeking, but the issue was that I was both asking the wrong questions and viewing them through the lens of what I wanted to believe. And so, uncomfortably, the conscious understanding has come much later, years after the body of work was completed. And the same thing happened with the following project that is yet unreleased. With my latest body of work, I am attempting to bring the lessons forward, but I am also finding that I am approaching my craft in a very different way now.

That isn’t to say that the act of creating was futile, but that it was working in ways that I could not understand at the time. My psychotherapist would say, “your creative process knows the path through this landscape, you just don’t trust that you know how to walk it”. And so, I think the power that we all hold as creatives is our ability and inner-strength to be pathfinders into the unknown.

CB: As a photographer working with deeply personal and introspective themes, what do you hope viewers take away from “Skeleton Woman”? Do you envision it as an inspiration for their own self-reflection, or perhaps as a nod to the universal nature of confronting one’s own past?

SH: I am very passionate about the often-undiscussed introspective strengths of Photography and so I think the project really speaks to that. But, I also hope that people take away that “it’s ok”. It’s ok to feel lost and disconnected, to not understand who you are or where you are going, that you feel lost or out at sea with no life-raft. I really admire David Lynch, and he often spoke to the idea that the artist does not have to suffer to create great art, that the more the artist is suffering the less creative they are going to be. A big part of his work was concerning the work of making the unconscious, conscious to unlock the full potential of the human being, so that you might live and work in more freedom. I see photography as a life-raft back to the self.

“Don’t fight the darkness, don’t even worry about it, simply turn on the light.” – Maharishi.

CB: Given the profound journey “Skeleton Woman” represents, both personally and artistically, how has this project influenced your approach to photography moving forward?

SH: “Skeleton Woman” was principally concerned with the process of reclamation. I find myself having reached a point where, for the most part, that journey feels complete and I am in a place of neutrality, a bit like being a newborn baby ready to experience the world for the first time. I am slowly starting to explore taking steps forward to understand who this Sasha is, and the camera is one of the vehicles of this exploration. I guess ‘seeking’ is a constant theme across my practice, but now it is rooted within a place of trust and potential vs. fear and scarcity.

::

Sasha Hitchcock is a photographer based in the UK. Her work is an investigation into her own psychological landscape and the role of creativity within expression, emotion, self-analysis and development. She frequently draws upon her family archive to inform her evolving practice and understanding of self. Sasha is interested in the role that human connection plays in curiosity and creative inquiry. Her work is increasingly moving towards providing a platform to develop an understanding of and practice unconditional love.

Sasha’s work has been featured in magazines and newspapers including The Times and The Telegraph and she has exhibited throughout the country. “Skeleton Woman” is her first monograph. For more information about the book and its upcoming release, please visit Orange Press at: https://orangepress.bigcartel.com/product/skeleton-woman

Location: Online Type: Black and White, Featured Photographer, Interview

Events by Location

Post Categories

Tags

- Abstract

- Alternative process

- Architecture

- Archives

- Artist residency

- Artist Talk

- Biennial

- Black and White

- Book Fair

- Car culture

- Charity

- Childhood

- Children

- Cities

- Collaboration

- Community

- Cyanotype

- Documentary

- Environment

- Event

- Exhibition

- Faith

- Family

- Fashion

- Festival

- Film Review

- Food

- Friendship

- FStop20th

- Gender

- Gun Culture

- Habitat

- home

- journal

- Landscapes

- Lecture

- Love

- Masculinity

- Mental Health

- Migration

- Museums

- Music

- Nature

- Night

- nuclear

- Photomontage

- Plants

- Podcast

- Portraits

- Prairies

- Religion

- River

- Still Life

- Street Photography

- Tourism

- UFO

- Water

- Zine

Leave a Reply