blog

REVIEW: ‘Trained Histories’ explores AI’s Intersection with Photography and Historical Narrative

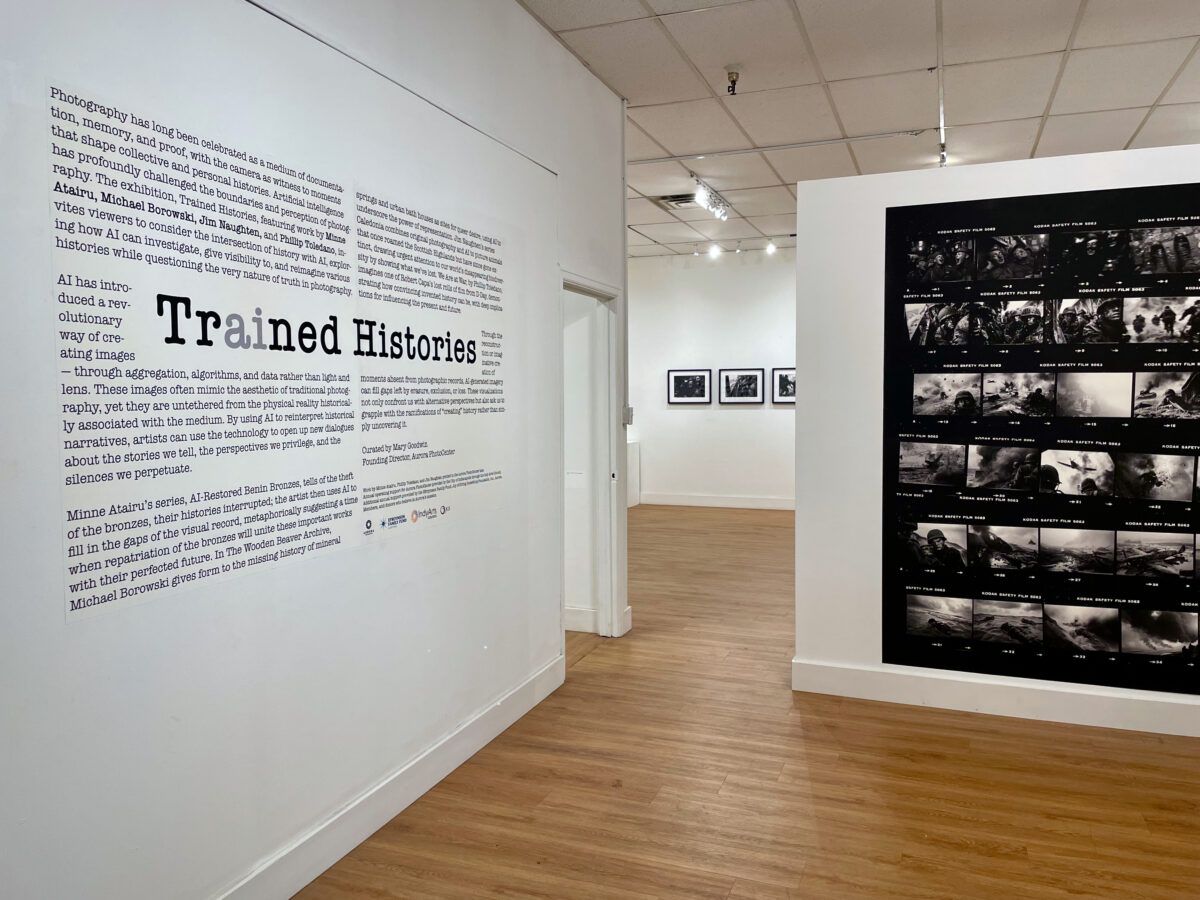

‘Trained Histories’ exhibition at Aurora PhotoCenter, Indianapolis, Indiana

In an age of AI-generated imagery, the question of ‘What is real?’ is more relevant than ever. The exhibition, ‘Trained Histories’, at Indianapolis’s Aurora PhotoCenter doesn’t shy away from this complex issue; instead, it invites us to explore our relationship with History and explore the evolving nature of photography itself. ‘Trained Histories’ is an engaging and thought-provoking exhibition and its images, whether AI-generated or rooted in traditional photography, also prompt viewers to consider the complex relationship between the medium and its subject matter.

The curated exhibition explores how artificial intelligence (AI), particularly Generative AI, is changing the arts and photography. I call this work photography and relate to it as photographic images. From its origin, photography has been seen as a tool for documentation, memory, and proof, capturing moments that shape our understanding of the world around us, of ourselves, and of history. However, AI introduces a new way of creating images, using algorithms and data instead of light and lenses. This challenges the idea of photography as a record of physical reality. It also challenges the idea of provenance and unique creative processes. The artists in the exhibition use AI to reinterpret historical narratives, raising questions about which stories are told, whose perspectives are privileged, and what silences are perpetuated. AI allows for the reconstruction or imaginative creation of moments absent from photographic records, filling gaps left by erasure, exclusion, or loss. This leads us to consider the implications of “creating” history rather than simply documenting it.

Curated by Mary Goodwin, founding director at Aurora PhotoCenter, ‘Trained Histories’ brings together four artists: Minne Atairu, Michael Borowski, Jim Naughten, and Phillip Toledano, each of whom are grappling with these questions head-on. The exhibition deftly explores how artificial intelligence is transforming photography and image-making and prompting a deeper consideration of how we understand history through the photographic lens.

The exhibition filled the main gallery space, and Goodwin’s curation emphasizes the dynamic dialogue between the artists’ distinct approaches. Some, like Naughten, begin with traditional photography and integrate AI, while others, such as Borowski, work primarily with AI-generated imagery which is presented via a historical photographic printing process. The result is a multi-faceted exploration of how AI can ‘investigate, give visibility to, and reimagine various histories,’ as the exhibition statement notes, pushing the boundaries of photographic expression. ‘Trained Histories’ acknowledges and celebrates the enduring power of the photographic image while also recognizing the new tools that are shaping its future.

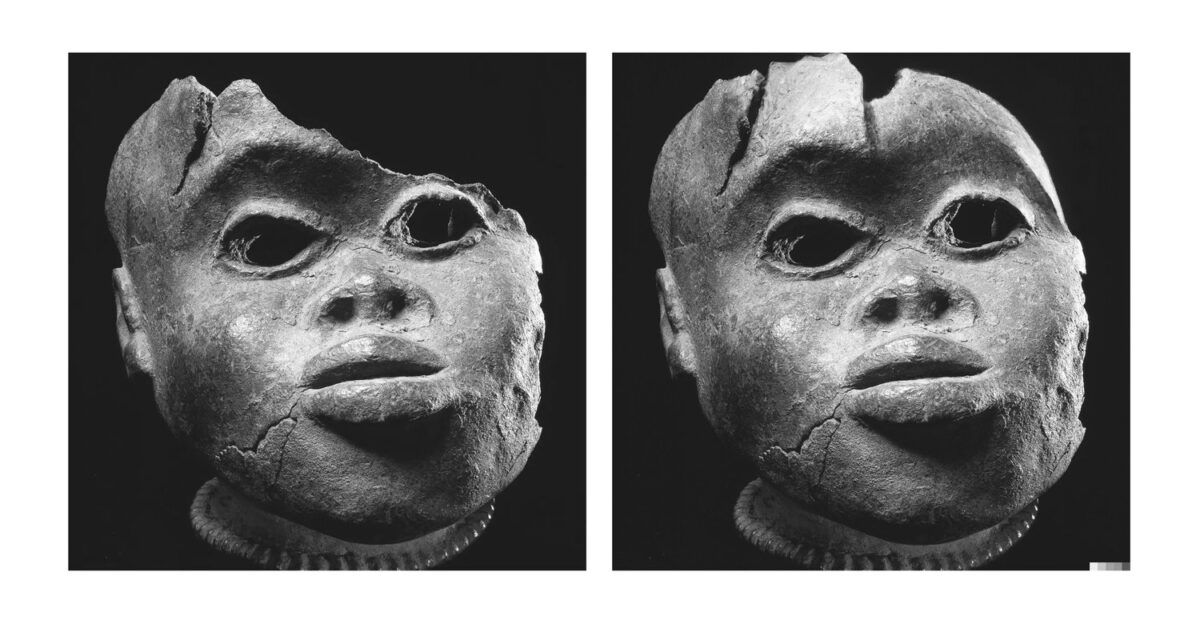

AI-Restored Benin Bronze Head by Minne Atairu

Minne Atairu’s AI-Restored Benin Bronzes powerfully uses AI to address the colonial theft of these artifacts, “filling in the gaps of the visual record” and metaphorically suggesting a future repatriation. Her employ of AI becomes a tool for historical repair, prompting reflection on what is lost—and what could be reclaimed, through the lens of photography. Because the work is presented in a very straight-forward manner, much like examples seen in an Art History textbook, and the use of AI is so subtle, her concept of manipulated or invented history as a vehicle for a metaphoric future-state repatriation was very strong. The repatriation of works of art from their original cultures is a current hot button topic in museum collections and raises important moral and ethical questions regarding ownership, colonial history, and cultural heritage. The manner in which these images are presented to viewers is so presumably factual, that one can easily see how viewers might accept the ‘repaired’ images to be fully authentic; perhaps making Atairu’s overall concept all the stronger for it.

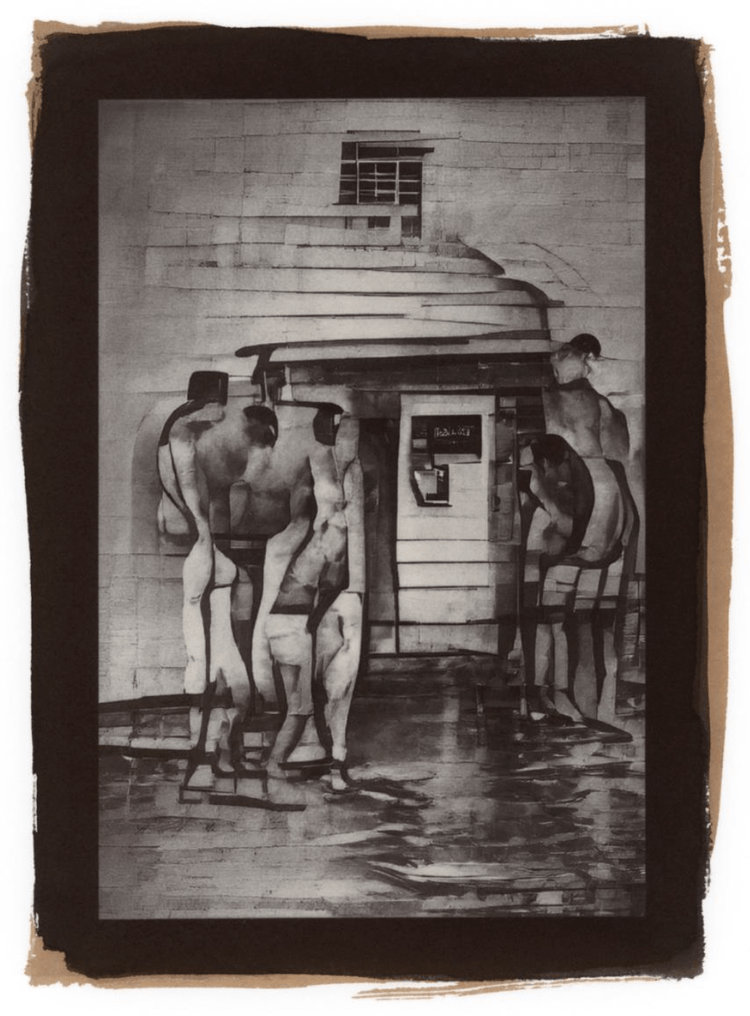

Document 0648 (Guests Arrive) © Michael Borowski

Michael Borowski’s The Wooden Beaver Archive imagines the hidden history of mineral springs and bathhouses as sites of queer desire. Borowski employs AI to create evocative “hazy, ambiguous mashups” that capture a sense of longing and the elusive nature of queer history. His small-scale salt prints made from digital negatives possess an almost tactile quality, like that of aquatints or intaglio printmaking, inviting close viewing and a sense of intimacy. Borowski’s prints are visually the least photographic-looking in this exhibition, but ironically they were made by one of the oldest traditional photographic processes. The work is abstract, yet figurative. Imagined, yet familiar. I found his amalgam of traditional and contemporary photographic practices to be inspirational and a true exploration of where photographers stand as artists in the 21st Century.

Wolves, 2023 © Jim Naughten

Jim Naughten’s Caledonia combines photography and AI to depict animals that once roamed the Scottish Highlands. Naughten’s work serves as a visually stunning reminder of our planet’s disappearing biodiversity. “These animals…represent both the history of biodiversity and its possible future,” the gallery text notes, through dramatic compositions printed in evocative color at 32 x 24 inches each. Each of the extinct animals looked like contemporary wolves, bears, or elk that one might still see in nature, or in a display at the Field Museum in Chicago This prompts the viewer to more easily consider the loss of animals they know or recognize. Yet Naughten’s use of colors of soft pinks and greens to evoke the Scottish Highlands presents a picturesque or romanticized aesthetic to his subjects. I’ve seen other examples of his work that uses more contrasting, jarring color sensibilities which I feel creates a heightened sense of conflict surrounding the loss of certain species, rather than idealizing the animals themselves.

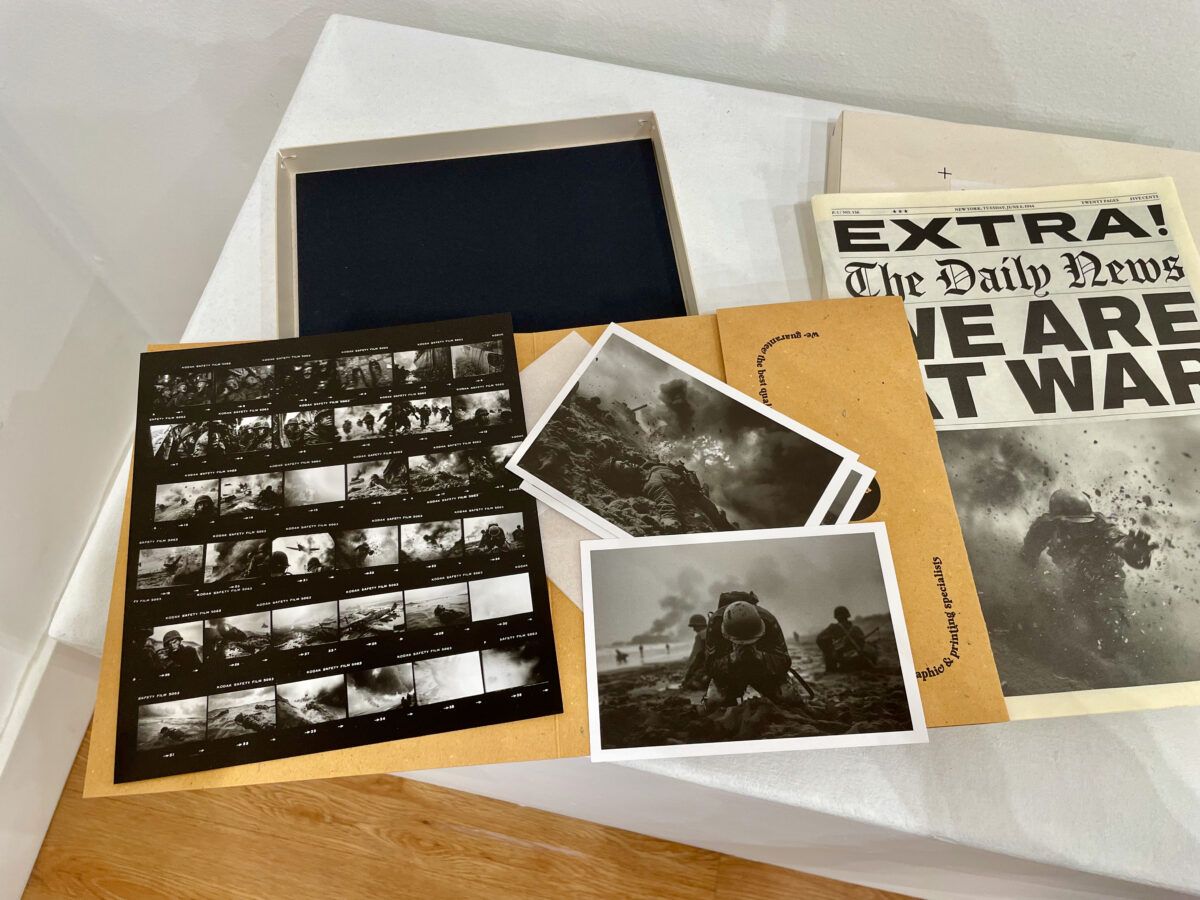

Plane Overhead © Phillip Toledano

Phillip Toledano’s We Are at War reimagines lost photographs by Robert Capa from D-Day. Toledano demonstrates how convincingly AI can fabricate history, raising important questions about the role of photography in shaping our understanding of the past. The inclusion of ephemera related to his project, such as a mock newspaper and a fabricated personal letter, enhances the immersive quality of the work. A powerfully engaging wall-sized print of Toledano’s mock contact sheet of images from We Are at War greets viewers at the gallery entryway. Upon reading the project statement, we are informed at the onset that Toledano is creating work that imagines what was lost from the vast majority of Capa’s damaged rolls of film shot during the Normandy invasion. As a result, the sense of questioning the ‘reality’ or history of the work is less natural. I never transcended the fiction, but enjoyed it nonetheless and found myself admiring how well the images looked like Capa’s work and “real” combat photojournalism of the time. Toledano’s AI prompts were adept at evoking a heightened sense of drama, shallow depth of field, and believable details, subjects and expressions of the ‘people’ shown in the photos.

‘Trained Histories’ definitely avoided the pitfall of displaying work that reaches for a dazzling display of technical ‘wow factor’ alone. So often in mass media and social media we see fantasy-based images engineered to push the boundaries of reality. All sizzle, no steak. But each artist in ‘Trained Histories’ utilized the primary tools of photography, both traditional and AI-driven, to create very compelling and thought-provoking images. The exhibition showcased a diverse range of technical approaches, from Borowski’s use of early AI models and salt printing to Naughten’s combination of photography and digital processes. Atairu’s work is conceptually strong, and Toledano demonstrates a mastery of visual storytelling.

Goodwin’s curation was key to the show’s success. She skillfully brings together artists who are all working with the concept of memory and the past, but with very different approaches and techniques, creating a dynamic and engaging dialogue about the nature of history and truth, and the evolving role of photography. ‘Trained Histories’ also taps into a central topic of our time: the blurring of lines between truth and fiction in the digital age. As AI becomes more sophisticated, its ability to create convincing realities raises important questions about the nature of photography, memory, and history. The show implicitly asks: ‘Is this photography?’ and, more broadly, ‘What constitutes a reliable record in an era of plastic media?’

The exhibition also highlights the exploration of AI’s training; millions and millions of images forming the basis of its visual vocabulary, which connects to current debates about AI’s impact on art and culture, and the very definition of photography. Of course this is not the first time photography has faced an existential crisis. From the transition from analog to digital, which was seen by many as the death of “true” photography, to the advent of Photoshop, which allowed for seemingly limitless manipulation of the photographic image, the medium has constantly been forced to redefine its boundaries. Even the rise of computational photography in smartphones, with its ability to combine multiple images and enhance scenes in ways previously impossible, has challenged our understanding of photographic truth. Now, the arrival of generative AI, capable of creating entirely new images from textual prompts, represents yet another paradigm shift.

Each of these technological advancements has been met with resistance from those who fear it will destroy the essence of photography. Yet, each time, the medium has adapted and evolved, incorporating the new tools into its ever-expanding definition. Goodwin creates a space for dialogue and reflection on the evolving nature of the photographic image and its crucial role in shaping our understanding of the world. This compelling exhibition smartly places AI within this historical context, acknowledging the unease it may provoke while also recognizing its potential to expand the possibilities of photographic expression.

Ephemeral items from ‘We Are at War’ © Phillip Toledano

::

Aurora PhotoCenter supports visual artists working in photography through exhibitions, residencies, workshops, visiting artist talks, and access to creative tools. As the only nonprofit in Indiana devoted exclusively to photography, Aurora is an essential hub for the medium in our arts community. Aurora also serves as a bridge between local artists and the greater photographic community, with a regional, national, and international scope. Aurora is passionate about photography’s emotional and social power as an art medium in its own right. To learn more about the organization’s workshops, exhibitions, visiting artists and programs, please visit their website.

Location: Indiana, Indianapolis Type: Essay, Exhibition

Events by Location

Post Categories

Tags

- Abstract

- Alternative process

- Architecture

- Archives

- Artist residency

- Artist Talk

- Biennial

- Black and White

- Book Fair

- Car culture

- Charity

- Childhood

- Children

- Cities

- Collaboration

- Community

- Cyanotype

- Documentary

- Environment

- Event

- Exhibition

- Faith

- Family

- Fashion

- Festival

- Film Review

- Food

- Friendship

- FStop20th

- Gender

- Gun Culture

- Habitat

- home

- journal

- Landscapes

- Lecture

- Love

- Masculinity

- Mental Health

- Migration

- Museums

- Music

- Nature

- Night

- nuclear

- Photomontage

- Plants

- Podcast

- Portraits

- Prairies

- Religion

- River

- Still Life

- Street Photography

- Tourism

- UFO

- Water

- Zine

Leave a Reply